On the so-called universality of protracted people’s war

PRISM editors are posting below the full text of a major response by Andy Belisario to the simmering debate on the “universality of people’s war”.

ON THE SO-CALLED UNIVERSALITY

OF PROTRACTED PEOPLE’S WAR

By Andy Belisario

31 August 2019

Introductory note

Two articles by a certain Ard Kinera, “Defend and apply the universality of Protracted People’s War!” and “Again in defence of the Universality of People’s War,” have been posted respectively on 6 June 2019 and 26 June 2019 in response to Jose Maria Sison’s two articles on the same subject. Kinera’s articles were posted originally on the TFM site (https://tjen-folket.no) and reposted the same day on the Democracy and Class Struggle site (https://democracyandclasstruggle.blogspot.com). Since Kinera is raring for direct polemics on the question and feels short-changed by Sison’s replies, I’ll indulge him.

Before I comment on his articles, let me pose the question as directly as possible: Is Mao’s strategy or theory of protracted people’s war one that has universal validity in the present era, and particular applicability in capitalist countries?

Kinera will most probably answer a definitive “Yes”, while I say “No, generally”—with certain qualifications and clarifications that will be presented further below. I will also show that Kinera is wrong not only on this question, but on a number of related questions particularly raised in his polemics with Sison.

“Protracted people’s war” vis-a-vis “people’s war” as a generic term

Kinera asserts: “Maoism puts forward the universality of People’s War strategy, puts this forward as the sole military strategy of the international proletariat, applicable in each and every country applied concretely in accordance to the different concrete conditions.” In another article he says in no uncertain terms: “[T]o be Maoist is to adhere to the universality of Protracted People’s War.”

He also says: “The Maoist principle that upholds Protracted People’s War … that establish in theory the universality of People’s War in each and every country of the World, is only established with the summation and synthesis of Maoism done by Chairman Gonzalo and the Communist Party of Peru. It was only part of doctrine since 1980, and especially since the General Political Line of the Peruvian Communist Party was established in 1988. It is thus quite new. And by then it was only one single Party in the World, adhering to this line.”

Take note that in his two articles, Kinera sometimes uses the term “protracted people’s war” and at other times simply “people’s war”. But it’s clear, especially when he argues vs. Sison, that he treats the two as interchangeable terms in the context of the theory’s “universality.”

This is a crucial weakness in Kinera’s arguments, since the protracted character of the people’s wars that liberated China and Vietnam has a precise socio-economic context and political-military meaning for agrarian or semifeudal countries that are oppressed by imperialism as colonies or semi-colonies. It is not merely expressed in numbers of years that armed revolutions in industrial countries could quantitatively measure up to.

Kinera also implies that the application of this universal theory of people’s war in different countries is a matter of simply “being flexible in tactics,” ergo, is not a question of difference in strategic line. This is another flaw, because it implies that CPs need only to concern themselves with tactics and no longer need to define their own strategies based on the particularity of their own countries—because, after all, their dear Gonzalo has already defined the Maoist “sole military strategy” of PPW for them!

The true universality of people’s war

The true universality of the term and concept of “people’s war” is that of the justness and historic role of armed revolution everywhere throughout the world when waged by exploited and oppressed classes to overthrow exploiter and oppressor classes.

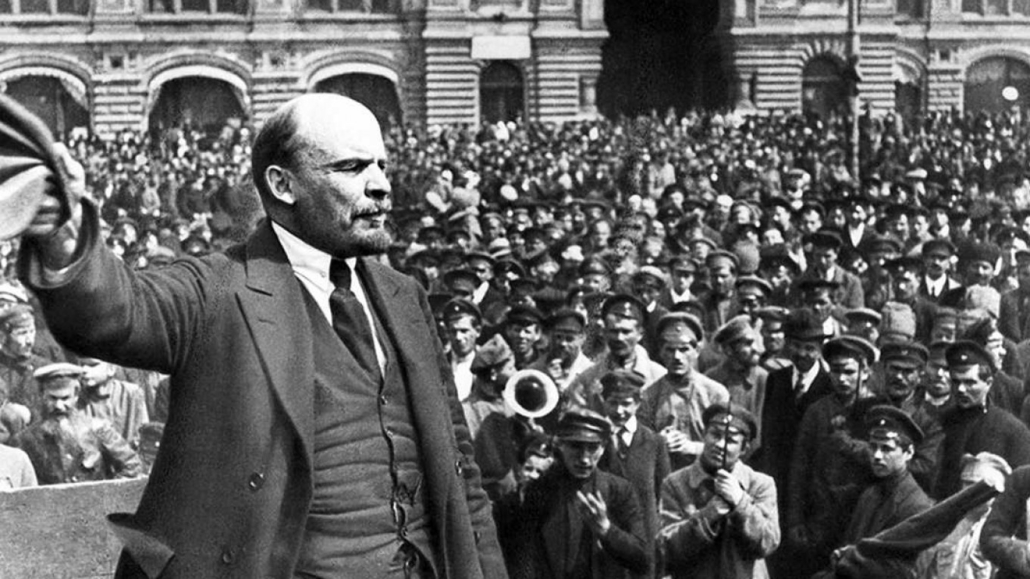

Marx and Engels had long developed this theory on the necessity of armed revolution by the masses of toiling people led by the working class, further clarifying the need to smash the existing bourgeois state machinery and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat in order to pursue and complete the socialist revolution. The basic principles of armed revolution by the proletariat and other allied classes were further elaborated by Lenin in his many works.

So, yes, in this sense, there should be no debate about the universal applicability of people’s war in all countries ruled by the big bourgeoisie and its reactionary allies. Had Kinera kept his polemics within these bounds, about “people’s war” being the equivalent of “armed revolution,” then there would be essentially no debate on the question.

However, Kinera glosses over two important corollaries to this fundamental principle of Marxism-Leninism. First, his arguments assume (even though not directly) that a revolutionary situation currently (or perennially) exists in all countries. Therefore all communist parties (CPs), if they are truly engaged in revolution, must adopt a corresponding military strategy and place armed struggle on their practical work agenda. And second, he insists that the Maoist strategy of protracted people’s war is applicable to industrial capitalist countries.

I will take these two corollary questions separately.

On the concept of revolutionary situations

While the fundamental task of armed revolution is axiomatic for all Marxist-Leninist parties (not just Maoist parties), it is not a dogmatic imposition that disregards concrete conditions. It doesn’t oblige all these parties to adopt armed struggle as the main form of struggle in their countries, to implement a corresponding military strategy for seizing political power, and to immediately start combat preparations and build combat formations.

The crucial question to ask is this: Is there a developing revolutionary situation in the country, or not? If there is no such revolutionary situation on the horizon, then it will be putschist if not suicidal for a party to mobilize an army and wage armed struggle in an attempt to seize political power. If there is such a developing situation, then preparing for armed struggle and mobilizing all forces under the correct military strategy certainly becomes an urgent and practical question.

The concept of “revolutionary situations” should be familiar to anyone who seriously studies Lenin’s works. From 1905-06 onward, Lenin had identified and described in detail the basic elements of a revolutionary situation through a close study of the 1905 Revolution. He further deepened his grasp of the concept in 1917. In “Left-Wing” Communism: an Infantile Disorder (1920), he summarized the necessary conditions for the existence of such a situation:

The fundamental law of revolution, which has been confirmed by all revolutions, and particularly by all three Russian revolutions in the twentieth century, is as follows: it is not enough for revolution that the exploited and oppressed masses should understand the impossibility of living in the old way and demand changes; what is required for revolution is that the exploiters should not be able to live and rule in the old way. Only when the “lower classes” do not want the old way and when the “upper classes” cannot carry on in the old way can revolution win. This truth may be expressed in other words: revolution is impossible without a nationwide crisis (affecting both the exploited and the exploiters). It follows that revolution requires, firstly, that a majority of the workers (or at least a majority of the class-conscious, thinking and politically active workers) should fully understand that revolution is necessary and be ready to sacrifice their lives for it; secondly, that the ruling classes should be passing through a governmental crisis which would draw even the most backward masses into politics (a symptom of every real revolution is a rapid tenfold and even hundredfold increase in the number of representatives of the toiling and oppressed masses—who have hitherto been apathetic—capable of waging the political struggle), weaken the government and make it possible for the revolutionaries to overthrow it rapidly.

Lenin of course assumed the existence of a proletarian revolutionary party and its correct leadership of the masses as an additional necessary condition for such a revolution to advance and win victory.

Sison reiterates this basic Leninist view when he says, in Basic Principles of Marxism-Leninism: A Primer (1981-82):

In either capitalist or semifeudal country, armed revolution is justified and is likely to succeed when objective conditions favor it and the subjective factors of the revolution are strong enough. Objective conditions refer to the situation of the ruling system. A political and economic crisis of that system can become so serious as to violently split the ruling class and prevent it from ruling in the old way. The ruling clique engages in open terror against a wide range of people and is extremely isolated. The people in general, including those unorganized, are disgusted with the system and are desirous of changing it.

The subjective factors of the revolution refer to the conscious and organized forces of the revolution. These are the revolutionary party, the mass organizations, armed contingent, and so on. To gauge their strength fully, one has to consider their ideological, political and organized status and capabilities.

The objective conditions are primary over the subjective factors. The former arise ahead of the latter and serve as the basis for the development of the revolutionary forces. The Communist Party cannot be accused of inventing or causing the political and economic crisis of the bourgeois ruling system.

In short, an armed revolution can only be justified and possible when objective conditions favor it (serious political and economic crisis and violent splits among the ruling classes, who can no longer rule in the old way, while the broad masses are disgusted with the system and no longer want to live in the old way). But the proletarian party must do its work well to develop the revolutionary forces, by undertaking serious and long-term preparations even before the revolutionary situation sets in.

The problem with Kinera is that he disregards the matter of objective conditions in specific countries, the level of crisis, the political behavior of the ruling classes, the range of responses by various political forces, the level of consciousness and readiness for struggle of the masses, and thus, a realistic evaluation of whether a revolutionary situation really exists or is at least a developing trend.

Mao on the strategy of protracted people’s war

From 1917 all the way through the 1940s, Lenin and Stalin—through their writings and through the Comintern—had consistently educated the CPs and revolutionaries of their time about formulating and implementing the correct strategy and tactics appropriate to the class structure, history, balance of forces, and concrete conditions of their corresponding countries.

Lenin, Stalin and the Comintern warned the other CPs particularly in the 1920s and 1930s of the danger of “Left-wing” infantilism, brash insurrectionism and military adventurism, especially since the victories of the Bolshevik party and the young Soviet state inspired these other CPs to emulate and replicate (sometimes dogmatically) the Russian model, often to reject the painstaking and seemingly non-revolutionary work within bourgeois parliament, reactionary trade unions and the like.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) especially under Mao had learned and benefited much from the Communist Party of the Soviet Uniion (CPSU) and Comintern, so at first they followed the strategy and overall tactics of the Russian revolution. Due to the great differences between Russia ca. 1900-1920s and China ca. 1920s-40s, however, the Mao-led CCP eventually developed its own strategy and tactics, which would lead to nationwide victory 22 years later and would be emulated by other CPs in many countries under the popular rubric of “protracted people’s war” (PPW).

The people’s war in China’s new-democratic revolution had fundamental commonalities with the 1917 October revolution but followed a distinctive strategy that was, in many ways, the latter’s opposite. The most crucial difference was that in contrast to capitalist Russia, the main force in semifeudal China was the peasantry in its huge numbers, and agrarian revolution was the main content. This meant that the main area for developing Red political power was in the vast rural areas while the ruling reactionary regimes could entrench themselves for quite some time in the cities.

There was indeed in China, throughout the first half of the 20th century, an increasingly favorable revolutionary situation as defined by Lenin in 1920. But still, the armed revolution had to start with small and weak forces relative to the size and strength of the counter-revolutionary forces. The process of overcoming the tremendous unevenness, accumulating strength in the countryside and eating up the enemy forces piece by piece, would take some time before the revolutionary forces were ready to take the cities and win nationwide victory.

It was on such comprehensive basis that Mao arrived at the necessary conclusion that, when compared to the relatively rapid process of armed seizure of political power in Russia, the process in China would be more protracted. This is the substantial meaning of protractedness, not merely the number of years of war. Mao would later elaborate this main theme to clarify other aspects specific to China’s PPW, such as the role and principles of guerrilla warfare, army building, base-building, and the three strategic stages of the war.

The Maoist strategy of PPW and many of its operational and tactical principles clearly remain applicable, and flexible enough to be adopted further, to the different conditions in various countries that are semi-feudal or principally pre-industrial due to imperialist rule and plunder. On this there is no fundamental question, and we will not dwell much further on this point.

On armed struggle in capitalist countries

The question however remains: What should be the strategy and tactics for armed revolution in capitalist countries? Will the Maoist strategy of PPW also apply? Sison rightfully says a different non-PPW strategy should apply. But Kinera insists that Maoist PPW strategy applies, even as he sometimes drops the term “protracted”: “Maoists define revolution just simply as People’s War, universally applicable also in the imperialist and mainly urbanized countries.”

Since Kinera (and his idol Gonzalo) invoke Maoism as their framework, let us then go back to what Mao actually said on the matter. We quote from Mao’s Problems of War and Strategy, written in 1938 as a well-known pillar of his military writings and major source of PPW theory:

The seizure of power by armed force, the settlement of the issue by war, is the central task and the highest form of revolution. This Marxist-Leninist principle of revolution holds good universally, for China and for all other countries.

But while the principle remains the same, its application by the party of the proletariat finds expression in varying ways according to the varying conditions. Internally, capitalist countries practice bourgeois democracy (not feudalism) when they are not fascist or not at war; in their external relations, they are not oppressed by, but themselves oppress, other nations. Because of these characteristics, it is the task of the party of the proletariat in the capitalist countries to educate the workers and build up strength through a long period of legal struggle, and thus prepare for the final overthrow of capitalism. In these countries, the question is one of a long legal struggle, of utilizing parliament as a platform, of economic and political strikes, of organizing trade unions and educating the workers. There the form of organization is legal and the form of struggle bloodless (non-military). On the issue of war, the Communist Parties in the capitalist countries oppose the imperialist wars waged by their own countries; if such wars occur, the policy of these Parties is to bring about the defeat of the reactionary governments of their own countries. The one war they want to fight is the civil war for which they are preparing. But this insurrection and war should not be launched until the bourgeoisie becomes really helpless, until the majority of the proletariat are determined to rise in arms and fight, and until the rural masses are giving willing help to the proletariat. And when the time comes to launch such an insurrection and war, the first step will be to seize the cities, and then advance into the countryside’ and not the other way about. All this has been done by Communist Parties in capitalist countries, and it has been proved correct by the October Revolution in Russia.

We repeat and underscore what Mao said in no uncertain terms: The task of the proletarian party in the capitalist countries is “to educate the workers and build up strength through a long period of legal struggle… of utilizing parliament as a platform, of economic and political strikes, of organizing trade unions… There the form of organization is legal and the form of struggle bloodless (non-military). … And when the time comes to launch such an insurrection and war, the first step will be to seize the cities, and then advance into the countryside…”

The contrast is stark as day and night: Mao says that PPW does not apply to capitalist countries (“when they are not fascist or not at war”), while Kinera insists it does. Mao (reiterating Lenin on the same question) says that the way to build mass strength towards eventual armed insurrection in capitalist countries is through a long period of legal struggle. Quite the opposite, Kinera says this “Petrograd model” is a “tired old strategy.”

On this point alone, Kinera’s entire house of cards about the “universality of protracted people’s war” collapses into a heap. He claims to be Maoist but doesn’t really get Mao’s teachings. He is shown up to be an infantile Maoist, or worse, a fake Maoist.

The specific characteristics of people’s war in capitalist countries

In his article on the same question, Sison rightfully asserts: “In industrial capitalist countries, the proletarian revolutionaries cannot begin the revolutionary war with a small and weak people’s army in the countryside and hope to use the wide space and indefinite time in the countryside to sustain the war.” He thus warns of the folly of applying the PPW strategy (“surrounding the cities from the countryside”) in capitalist countries.

Kinera says: “Who made this the defining factor of People’s War? Not the Communist Party of Peru at least. It is crystal clear from all Maoists … that the path of surrounding the cities is not a universal law of PPW.” Kinera’s problem is that he swallows Gonzalo’s distorted definition of Maoism and PPW, forgets to check with Mao’s original military writings and theory about PPW, and then complains—on that hopelessly confused basis—that Sison is making things up about the factors for a successful people’s war.

Sison’s point is that in the highly urbanized and other highly developed areas of capitalist countries, under current conditions when there is no full-scale war and revolutionary crisis, a people’s army that launches tactical offensives with no sizeable mass base (at least equivalent to rural guerrilla bases in countries such as China and Vietnam) will be hard-pressed to counter-maneuver, employ guerrilla tactics, retain initiative, and hit back at the enemy’s weak points, and much less be able to consolidate and expand their bases. In the most realistic and practical terms, such a people’s army cannot sustain itself and continue to grow into bigger formations that combine military work, political work, and production work (as Mao defined the tasks of a people’s army).

Such a people’s army can only do so when other crucial factors favorable to the armed revolution’s advance are at play such as an intense crisis that has greatly weakened the enemy state and demoralized its rank-and-file, extensive and expanding political base engaged in mobilizing the masses of toiling people, and of course correct Party leadership.

Sison rightly asserts: “As soon as that army [in a capitalist country] dares to launch the first tactical offensive, it will be overwhelmed by the huge armed forces and the highly unified economic, communications and transport system of the monopoly bourgeoisie.”

Kinera counter-argues that “this is simply not true.” Then he proceeds to mention Italy’s Brigada Rossa, Germany’s “Red Army Faction”, Japan’s “JRA”, the US Weatherman Underground and “Black Liberation Army”, the Basque ETA, and “several active armed groups in Ireland,” all of which continued to operate for a number of years before they folded up. He explains their failure this way: “… most of these groups were not armed with the omnipotent ideology of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism. They were not led by a militarized Maoist Communist Party. … In most cases, the groups capitulated due to loss of morale or lack of Ideology and political leadership! That is true of many of these groups.”

In short, Kinera focuses exclusively on subjective factors for the failures, e.g. “loss or morale” or “lack of ideology and political leadership” by a “militarized Maoist CP.” He avoids giving weight to the objective factors, which were stressed by Lenin and Mao. In nearly all cases he mentioned, there were no favorable objective conditions for an armed revolution to advance and win, in addition to big gaps in preparing the masses (through open and underground channels) for eventual armed struggle. It remains for genuine Marxist-Leninist (ML) or Marxist-Leninist-Maoist (MLM) parties—certainly not Kinera and his Gonzaloite friends with their “militarized CP” mindset!—to make comprehensive summings-up to explain the eventual failures and draw lessons.

On Kinera’s vision of PPW in capitalist countries

But let us allow Kinera another chance to describe in detail his “Maoist PPW strategy” for capitalist countries.

If it is to be a protracted people’s war, as in Mao’s China and Ho’s Vietnam, then where in the social and geographic terrain of a capitalist country, and how exactly, will the organs of revolutionary political power be organized and sustained?

Remember that the essence of protracted people’s war is not simply to maintain fighting teams that use guns—which the fascists, the Mafia, and conspiratorial terrorists also do—but to mobilize the masses in the armed struggle in order to dismantle the bourgeois-reactionary state machinery (especially its armed forces) step by step and in likewise fashion to build the revolutionary state machinery and use it to defend the people’s gains.

If it is to be a genuine revolutionary war, and not just idle prattle or showing militancy in street battles against the police, what is to be the main form that war is going to take? Armed insurrection in the cities? Pockets of guerrilla/partisan warfare in populated areas that will either grow into or support wider theaters of regular mobile warfare, or grow into (or support) armed insurrections? What types of military formations will be built and deployed, and from which main social class?

The Bolsheviks in Lenin’s time, the CCP in Mao’s time, and the Communist Party of the Philippines in the current period, went into extensive and detailed description of their strategic, operational, and tactical principles in order to flesh out their theory and vision of armed revolution. Since Kinera disdains “hiding our intent from the masses,” then this is his chance to explain his own version of “Maoist military strategy and tactics” in detail. My guess is that it will be a revised edition of Gonzalo’s Peru ca. 1988, transplanted to current-day Europe. But Kinera should further expound.

On the military theory of the international proletariat

Despite Kinera’s misplaced flattery, Mao was not the original proponent or first theorist of people’s war as “the military theory of the international proletariat.” For Kinera (or his idol Gonzalo) to make this claim is a disservice to other great communist leaders who made equally valuable contributions to the proletariat’s military theory and practice, as expressed in the strategic, operational, and tactical principles that they adopted for their respective revolutions and are now available for study and creative application by all revolutionaries of the world.

Marx and especially Engels closely studied military theory based on existing armies and military doctrines of their time, actual wars and battles not just among European states but in the mass uprisings of the 1848 revolution, the 1871 Paris Commune, and anti-colonial insurrections in Asia. Lenin led the Bolsheviks in turning the principles he expounded (e.g. in State and Revolution) into the practical tasks of organizing the Bolsheviks’ armed uprising, of building the Red Army from partisan units and reorganized tsarist troops, and of organizing Soviet power in the many localities wrested from the White armies. Stalin shared his rich experience acquired as a field commander in the Civil War, and encouraged other Soviet commanders to draw from their experience of partisan warfare (e.g. a growing understanding of deep operations with a peasant rear in a long war) and systematize these in the fledgling institutes of military science and training.

Mao of course made immense contributions to proletarian military theory based on his vast leadership experience in the long years of Chinese revolution, as did Ho Chi Minh, Le Duan and Vo Nguyen Giap in the case of the Vietnamese revolution, and Sison in the case of the Philippine revolution. All of them successfully applied proletarian military theory to practical questions of people’s war in their respective countries, and in the process enriched such theory.

However, these communist leaders did not set out to “synthesize” a “universally applicable theory” on how to wage armed revolution, or forge some “military theory of the international proletariat,” as Kinera claims Gonzalo had done. In fact, these great leaders repeatedly emphasized “concrete analysis of concrete conditions” and carefully applied theory to grapple with the specific characteristics of their own countries and solve concrete problems of their own revolutions.

In one line of argumentation, Kinera even cites Thomas Marks, a US counter-insurgency expert, to show that a bourgeois-reactionary expert agrees with his distortions about the content and value of Maoist military strategy. Both Kinera and Marks bloat up notions of “asymmetric warfare” into some sort of “universal Maoist principle”. In the process, they set aside the historically specific class basis of Mao’s PPW strategy (a rural peasant war led by the proletariat) and its concrete social setting (semi-feudal country oppressed by imperialism). To strengthen his weak arguments about the universality of PPW, Kinera even goes as far as to arrogantly claim: “What bourgeois experts [like Marks] understand, many revolutionaries fail to grasp.”

In another line of argumention, Kinera belittles the proletarian strategy for armed revolution in capitalist countries, as forged by the Bolsheviks: “The plan to dogmatically repeat what they conceive as the October path of Lenin, more than 100 years later and against an enemy that has studied insurrection and how to beat it for just as long, as some kind of surprise attack, is extremely naive.” In short, Kinera believes that the all-wise enemy “has studied [Bolshevik-style] insurrection and how to beat it,” but in the same breath agrees with counter-insurgency expert Marks that “guerrilla warfare is universally applicable.”

On a “militarized” Communist Party

What exactly is meant by a “militarized Communist Party”? Does it mean that the principle of democratic centralism, which applies to the essentially civilian and voluntary membership of a CP, will be replaced by a military command structure and its concomitant military law and military discipline? If so, that would be a monstrous distortion of the principles of proletarian Party life and would reflect an extreme case of purely military viewpoint or militarism.

Or does a “militarized Communist Party” simply mean that the Party operates underground outside of base areas, and that Party members are encouraged to learn military work, e.g. be familiar with guns and work in tight teamwork with near-military discipline? But CPs that lead armed struggles are already expected to adopt such methods, yet have no need to enshrine it as a principle on the same level as the name “Communist Party” or “Bolshevized party” and the practice of democratic centralism.

If the term simply means that CPs cannot viably combine open and underground channels of work, legal and illegal methods, but must choose one or the other, to either be “militarized” or be guilty of “legalism”, then Kinera is an infantile brat whose coloring pens are limited to blacks and whites.

On protracted preparations for armed revolution in capitalist countries

Sison rightfully says: “[T]he term “people’s war” may be flexibly used to mean the necessary armed revolution by the people to overthrow the bourgeois state in an industrial capitalist country. But definitely, what ought to be protracted is the preparation for the armed revolution with the overwhelming participation of the people.” He explains, in his various writings, about the need for a strategy for accumulating strength through the legal mass movement combined with underground methods when objective conditions for armed struggle do not exist.

In fact, it was by such Bolshevik strategy that Lenin greatly contributed to, that powered the two 1917 Russian revolutions to victory, and which he brilliantly expounded at the tactical level in his work “Left-Wing” Communism as applicable to many other capitalist countries during the Comintern period prior to World War II.

Kinera accuses those proletarian revolutionaries in capitalist countries who are patiently accumulating strength in the Leninist way (which he labels “Western accumulationists”, including Sison) as “opposed to People’s War but posing as revolutionary,” as practising “reformism and legalism.” He rejects “the line of accumulation of forces through protracted legal struggle” as just passively waiting for the necessary objective conditions to arrive. He rants: “No wonder we have waited for a long time, and by this method one could go on forever, was it not for the fact that imperialism is doomed. These people want to do revolution by doing everything but revolution!”

He complains: “Protracted, very protracted, preparation by all legal means and sometime in the future, an armed revolution. It must be said again and again, that this has never happened. Not in a 100 years has this happened, even though hundreds and thousands of groups and parties adhered to this strategy. And the practice of these groups and tendencies has always been more or less identical to the practice of the openly reformist forces.”

In short, Kinera disdains the work in reactionary trade unions and bourgeois parliaments that Lenin (in “Left-Wing” Communism and other works) had so patiently explained as important part of revolutionary tasks during a non-revolutionary period. Kinera disdains the very essence of mass line and painstaking mass work that Mao had so consistently reminded Communists to practice. He disdains the patient work of accumulating strength because he is too shortsighted to see its connection and eventual result in people’s war. He wants people’s war on the agenda, but is too impatient to build the strength needed to wage one in the future. He wants to see people’s war now.

And yet, when Sison asks Kinera to show what the so-called “Maoist” champions of “PPW in capitalist countries” have achieved so far, the latter could only shrug off the challenge with the cavalier remark: “We cannot really address the statement of no preparations being made. This might be true. It might not. … If anyone where to make such preparations, they should never tell Sison, since he feels obliged to inform the whole world of any such preparations and the seriousness of them.” So much for “not hiding our intent as Communists!” which he is so fond of invoking.

Sison’s remark about not seeing “any Maoist party proclaiming and actually starting” PPW in imperialist countries was obviously to show that truly serious Maoist formations in these countries see such course of immediate action as not viable for now. Kinera’s response to this is dishonest and disingenuous: he basically challenges Sison to publicly reveal “any Maoist party not adhering to the strategy of People’s War and being of such quantity and quality” (note that he dropped the word “protracted”). This is a cunning trap.

Kinera rejects the so-called “strategy of protracted legal accumulation to the brink of crisis and revolution” in capitalist countries as an “old strategy,” and chides Sison of being “never tired of the protracted legal accumulation of forces, in wait and want of the cataclysm” of crisis. But he doesn’t produce any arguments that show why such strategy is incorrect.

He simply condemns it as “the totally dominating strategy” of practically all Left forces in Europe, including those that “adhere to Mao Zedong Thought” (but not Gonzaloites). This shows that Kinera is a hopeless infantile sectarian who cannot even derive good points of tactical unity with other revolutionaries and progressives who do not kowtow to Gonzalo Thought.

Conflating the 1905 and 1917 Russian revolutions into “15 years of armed activity”

Kinera tries to prove the applicability of PPW in capitalist countries by conflating the three Russian revolutions into one: “The armed struggle of Russia in 1917 cannot be mentioned without also bringing forward the failed revolution of 1905. This was pretext to 1917. And the war lasted to 1921, over a span of 15 years, where there was a lot of armed activity not only in 1905 and 1917.”

In short, he conflates the three Russian revolutions into “a span of 15 years” during which there was “a lot of armed activity” (ergo, supposedly long years of armed struggle). Kinera thus dishonestly conjures an illusion of a continuous PPW in a capitalist country. He conveniently forgets about the years of reaction (1907-1910) when the revolution was in full retreat, and the years of revival (1910-1914) when the Bolsheviks pursued tactics combining illegal work (but not yet armed struggle!) with the “obligatory utilisation” of many legal channels including winning seats in the reactionary parliament.

Kinera says nothing about the waves of favorable objective conditions that underlay both 1905 and 1917 (including the Russo-Japanese war, World War I, and the ensuing severe crises). In doing so, he also belittles the patient process of accumulating strength in the open (and therefore essentially legal) workers’ movement as well as in the underground before the said crises, which took many years, and which resulted in economic and political strikes and the emergence of the Soviets prior to the actual armed mass uprisings.

On the size of the industrial proletariat in advanced capitalist countries

Kinera responds to Sison’s explanation on differences of class composition between capitalist and semi-feudal countries, which underlies revolutionary strategy and tactics, in this way: “We must ask ourselves, what countries is Sison speaking of? There is no country in Europe or North America at least, where the industrial proletariat is the majority.”

Again, Kinera is confused. Sison was clearly comparing the size of main productive classes in feudal vis-à-vis modern or industrial capitalist countries. In that regard, the industrial proletariat is indeed the majority class in capitalist countries compared to the peasantry. The peasantry, in turn, remains the majority class in feudal or semifeudal countries especially if other rural semiproletarians outside direct farming occupations are added up.

Kinera claims that “[those] employed in public or private services … outnumber the industrial proletarians in most imperialist countries.” He must be reminded that the modern industrial proletariat includes such service workers, insofar as their class situation is most analogous to industrial workers. They also do not own any industrial means of production; their income comes from the sale of labor power to the capitalists; and their role in services also involves operating powered and automated machinery for mass-producing commodities (although in the form of services and not discrete material goods).

Apparently, Kinera automatically excludes from the industrial proletariat those sizeable working masses employed in major service firms in transport and storage, communications and media, health, and so on. There is no such class as “service proletariat” mechanically separate from the modern industrial proletariat, as if they are boxed off from the intense class struggles and the aspirations for socialism. If at all, the bulk of workers in service industries are a powerful motive force for revolution—if only an ML or MLM party takes serious notice and conducts painstaking social investigation, mass work, and union-based economic and political mass struggles among them.

On winning the battle for democracy

Sison explains: “Even if the material foundation for socialism exists in capitalism, the proletariat must first defeat fascism, thus winning the battle for democracy, before socialism can triumph.” He was actually anticipating the convulsions of capitalist crises and the rise of fascism, which impels all proletarian revolutionaries to prepare for future armed conflict even prior to the actual socialist revolution. This was in fact the scenario that led to Communist-led forces waging extensive partisan warfare in Europe during World War II and even earlier during the Spanish Civil War.

Incongruously, however, Kinera goes ballistic and immediately screams about errors of “revisionism” and “peaceful transition from capitalism to socialism.”

It was Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto (1848) who first expressed the proletariat’s first revolutionary task in this manner:

We have seen above, that the first step in the revolution by the working class is to raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class to win the battle of democracy. The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible. (My underscore)

This concept (“winning the battle for democracy”) must be seen in multiple but related contexts. First, in the context of 19th-century Europe, the proletarian movement had to fight for bourgeois democracy as part of its first attempts to gain and exercise political power, as was shown during the 1848 revolutions.

Later (and especially after the 1871 Paris Commune), Marx and Engels concluded that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes” but had to smash the existing state machinery. Still, they continued to uphold the democratic republic as the best form for the proletarian dictatorship that would implement socialist democracy as a thousand times more democratic than bourgeois democracy.

At the same time, in many countries with substantial vestiges of feudalism and autocracy, they saw the need for the proletariat to lead and complete the bourgeois-democratic revolution as a prelude to the proletarian-socialist revolution. Finally, since imperialism also brought forth the conditions of fascism and inter-imperialist war, it presented a still broader arena for the proletariat to lead all democratic forces in anti-fascist and anti-imperialist wars as a prelude to or as an extra dimension of socialist revolution.

In this regard, Sison mentions the possibility of “organizing proletarians with firearms” (for sport, community self-defense, voluntary security) as one of many legal ways of preparing the advanced masses in capitalist countries for armed struggle—which is very different from immediately waging armed struggle. He mentioned “current constitutional and legal standards” as one of many considerations in openly acquiring arms. This question in fact becomes an increasingly popular issue nowadays given the rapid rise of violent (even armed) neo-Nazi and ultra-Rightist movements in Europe and North America and the need for a clearcut proletarian call for combating fascism on all fronts.

But here Kinera turns ballistic again. He argues about “strict gun laws in Europe” (which of course was not Sison’s point). He also wrongly associates Sison’s ideas with the creation of Russian workers’ militia (which emerged in the extremely revolutionary situation of 1917 and certainly was not just Trotsky’s idea but incorporated into the Bolshevik program). The Red Guards were a creation of the Bolsheviks and the masses, not Kinera’s idol Trotsky.

These are all opportunities for the proletariat to arm itself and seize power when the conditions are ripe, and make the necessary but calibrated or discreet preparations prior. But Kinera doesn’t see the underlying Marxist-Leninist logic. He is singular obsessed with the template of PPW (as “synthesized” by Gonzalo) needing to be implemented now; anything outside the template is branded as revisionism, reformism, or legalism.

On other pertinent matters

Like a hyper-active puppy, Kinera’s debating style is to seize on certain phrases he doesn’t like linguistically, to tug on bits of ideas that he relishes, and to chew on them until the whole thing turns into a sorry senseless mess. Then he barks at Sison for the sorry senseless mess.

Kinera throws a temper tantrum when Sison describes the claim about “the universality of Mao’s theory of protracted people’s war” as a mere “notion of some people.”

He even complains of Sison’s use of the terms “proletarian revolutionaries” and “the party of the proletariat” instead of “Communists” and “the Communist Party”. (The two sets of terms are synonymous or at least near-equivalent if one is not misled by pseudo-communists fixating themselves on a few terms and merely waving the communist party banner. But Kinera the nitpicker just has to have his snide comments in edgewise.)

Kinera repeatedly accuses Sison of being opportunist, of wiggling through “the narrowest cracks,” of “running away from the two-line struggle,” and of using “dishonest methods of debate” – just because his infantile mind doesn’t get Sison’s main points as well as nuanced handling of the issues at hand. He is enraged that Sison’s two articles do not name anyone, or even briefly name the Partido Comunista de Peru or quote “at least some of their documents.”

When Sison reminds readers that a Communist Party needs to take its clandestine tactics and underground methods seriously, and not publicly declare its intent to commence warfare or to build a people’s army “before the conditions are ripe for armed revolution,” Kinera labels Sison as an opportunist and launches into a sanctimonious lecture on the famous dictum in the Communist Manifesto: “The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims.” This guy is too funny if not too much of a nitwit!

Kinera and his group Tjen Folkdet lack self-awareness and self-criticalness. Since 1998, which is more than twenty one years ago, they have not advanced from a pre-party formation and have not become a revolutionary party of the proletariat or a Communist Party to lead the proletariat and people in any kind of armed revolution. Their protracted talk about PPW has not yet proven to be any different from the illusion of the social democratic and other reformists about the protracted evolution of capitalism to socialism.

Despite their mantra of PPW, they have not done anything to start any kind of people’s war in Norway or assist such war if any in some other industrial capitalist country or give any significant kind of help to the people’s wars going on somewhere else in the world. They still need to grow from their small-group status and infantile mentality by doing serious mass work among the Norwegian workers and engaging in truly MLM Party-building to be able to contribute more significantly to the resurgence of the world proletarian revolution against imperialism, revisionism and all reaction.

On real and fake Maoism

But enough of Kinera’s capers. Let us end with a most serious question of principle.

Kinera idolizes Gonzalo to high heavens, for his role in “synthesizing” Maoism: “Maoism was comprehensed only through the People’s War in Peru and that the PCP was the only Maoist Party in the world in 1982.” “[T]he content of Maoism was not clearly stated before 1982 and then only by the PCP.” “[It] is well known that when Maoism was synthesised for the very first time, it was done by Chairman Gonzalo and the Communist Party of Peru. This was finalized by the Party in 1982 in the midst of People’s War.”

These incredibly arrogant claims by Kinera (following his idol Gonzalo) is a brazen insult to Mao, who after his death apparently needed another thinker to “synthesize for the very first time” his well-known teachings and to pin on it the shiny new name Maoism. It is a historic slap at the Chinese Communist Party, which up to 1976 was led by Mao himself together with other proletarian revolutionaries, and which was guided by Mao’s theories (which was called Mao Zedong Thought and eventually Maoism).

Mao’s Selected Works, his many other writings and CCP documents ascribed to him, and unpublished talks (representing his immense contributions to Marxist-Leninist theory and revolutionary practice) have been in wide circulation outside China since the 1950s. These have been studied by countless proletarian revolutionaries in many countries, have been applied to varied conditions, and have inspired and helped guide many people’s wars and internal rectification movements. Mao’s works (and the theories of Maoism that run through them) remain publicly available for every serious revolutionary activist to study and grasp.

Kinera’s claim that PCP was the “only Maoist Party in the world in 1982” is a blatant lie, if only because the Communist Party of the Philippines had already been reestablished earlier in 1968 on the basis of its founding cadres’ firm grasp of Maoist theory and its application to concrete Philippine conditions. In Rectify Errors and Rebuild the Party (a major CPP document of reestablishment issued in 1968), Mao Zedong Thought was already repeatedly and correctly described as the acme of Marxism-Leninism in the current world era. The CPP has been assiduously building itself and achieving victories in people’s war on the basis of MLM since then, as its voluminous documents, publications, and study courses show.

Kinera and his kind of infantile communists are grossly ignorant of the pronouncements of the Chinese Communist Party under the leadership of Mao since the onset of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1966. Far ahead of Gonzalo, the Chinese communists have upheld the theory and practice of continuing revolution under proletarian dictatorship through cultural revolution in order to combat modern revisionism, prevent the restoration of capitalism and consolidate socialism.

They have considered the cultural revolution as the greatest and most original contribution of Mao to the development of Marxism-Leninism and the guarantee for imperialism heading for total collapse and socialism marching towards world victory in the next 50 to 100 years from 1969. The have regarded the cultural revolution as the hallmark of the third stage in the development of Marxism and as surpassing his major contributions in philosophy, political economy, social science, rectification movement in Party building and people’s war.

Despite his great theoretical and practical revolutionary achievements, Mao was modest enough to resist the superlative titles (except teacher) being addressed to him by his comrades. It took sometime for the comrades to gradually modify the reference to Mao’s theoretical work from “Mao’s thinking” to Mao Zedong thought (with a small “t”) and finally to Mao Zedong Thought (with a big “T”). The significant content and consequences of Mao’s theory and practice were already summed up and recognized upon his death in 1976.

It is laudable if indeed in 1982 Gonzalo was the very first to transcribe Mao Zedong Thought to Maoism. It is another matter whether his supposed “synthesis” of Maoism would surpass the summing up by Mao’s own loyal Chinese comrades. By itself, the transcription from Mao Zedong Thought to Maoism is not a great achievement. Marx berated Paul Lafargue in 1883 for using the term Marxism for revolutionary phrasemongering against the struggle for reforms. Even then, Karl Kautsky popularized the term Marxism and subsequently used it to deny the Marxist character of Lenin’s theory and practice, which he termed as Leninism.

To differentiate “Maoism” from “Mao Zedong Thought” is to nitpick and invent a false distinction. Even Gonzalo used the phrase Mao Zedong Thought until 1982. Whichever term is used, we certainly have no need for the dubious genius of a Gonzalo to “comprehense” or “synthesize” or canonize or reinvent it anew for the world’s benefit. He could not have added to the achievements of Mao himself after his death in 1976. It is pure nonsense to make it appear that the continuous significance and consequentiality of Mao’s theory and practice depend on the words of Gonzalo.

On Gonzalo’s revolutionary and opportunist record

The infantile or pseudo-Maoists characteristically use such expressions as Maoism and Gonzalo Thought to browbeat other people or trample on others as “revisionists” and “opportunists” without the concrete analysis of concrete circumstances and issues. As dogmatists and sectarians of the worst kind, they use such expressions as “Gonzalo is the greatest after Mao”, sounding like evangelists who proclaim Jesus is the Lord. Mistaking struggle mania for revolutionary struggle, they are quick to throw invectives and do not really engage in a serious substantive debate.“Gonzalo thought”, as painted by Kinera, is not ideology but IDOLOGY.

Kinera and his fellow dogmatists and sectarians are incapable of recognizing the egotism, immodesty and arrogance of certain leaders who wish to proclaim their universal greatness even before winning the revolution in their own country and who actually brand their own theories and practices with their own names, like Gonzalo Thought, Prachanda Path and Avakian’s Synthesis (to proclaim himself the great leader of the new wave after MLM).

Let us focus on the idol of Kinera. Gonzalo may be praised for founding the PCP (Sendero Luminoso) in 1969 under the guidance of Mariategui and Mao Zedong Thought. But despite his belief that people’s war can be started at the drop of a hat, Kinera does not take Gonzalo to task for being a sluggard, starting the people’s war only in 1980 (eleven years after the PCP-SL founding), so different from the CP of the Philippines being founded on December 26, 1968 and starting the people’s war on March 29, 1969 (three months after the CPP founding).

Despite his gross failures at building the united front as a political weapon from 1969 to 1992 , Gonzalo may still be praised for engaging in the building of the Party and the People’s Guerrilla Army up to late 1980s when without respect for the facts of the revolutionary armed struggle he invented the illusion of “strategic equilibrium” and proceeded to seek a “Left” opportunist shortcut to victory through urban insurrection. Inasmuch as he abhors stages, Kinera can praise Gonzalo for disregarding the probable stages in the development of protracted people’s war as previously defined by Mao. But Gonzalo is a gross violator of Mao’s teachings on protracted people’s war.

After his capture in 1992, Gonzalo was quick to captitulate to the Fujimori regime and become a Right opportunist by offering peace negotiations and peace agreement with the regime, causing costly splits among the members and supporters of the PCP-SL. Since then, the infantile Maoists have made a blanket denial of Gonzalo’s capitulation and Right opportunism despite subsequent manifestations of the truth since 1993, such as his public TV appearance, confirmation by his wife and testimonies of his lawyer who visited him weekly. On this basis, RIM started to become critical of Gonzalo’s behavior.

Notwithstanding his flip-flop from “Left” opportunism to Right opportunism, which has caused the people’s war to decline and nearly total defeat in Peru, Gonzalo deserves compassion for having been imprisoned for more than 27 years and for having suffered so many violations of human rights. The campaign to seek amnesty and release from prison deserves support and international solidarity, provided he does not call on the Peruvian revolutionaries to surrender and stop the people’s war even under the revisionist pretense that the people’s war can be resumed after his “genius” or “great thought” becomes available in the battlefield. ###

NDFP

NDFP

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!