Primer on China’s Revolution and Maoism, Part 2

This is Part 2 of the PRISM Primer on China’s Revolution and Maoism, drafted in 2021 on the occasion of the centennial anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China (CPC). The study material is offered to all socialists and anti-imperialist and democratic activists, and will be posted in 10 parts.

PRIMER ON CHINA’S REVOLUTION AND MAOISM

On the occasion of the 100th year of the Communist Party of China

Prepared by Andi Belisario for PRISM (Reissued 1 October 2022)

(Part 2. CPC founding, earliest phases of new-democratic revolution)

II. NEW-DEMOCRATIC REVOLUTION, EARLIEST PHASES (1921-27)

The 1921-1927 period covers the founding and earliest years of the Communist Party of China (1921-23), and the First United Front with the Kuomintang and the First Revolutionary Civil War (1924-27).

1. How did founding the CPC lead to revolutionary advances in the 1921-1927 period?

1.1 The founding of the CPC

From summer 1920 to spring 1921, radical Chinese activists became fully convinced that the time was ripe to establish the Communist Party of China (CPC) to consolidate the several dozens of Communists and several hundred activists of the Socialist Youth League. There were already several city-based collectives that considered themselves Party branches. Despite disruptions by anarchists among the prospective groups, these branches intensified discussions and chose delegates for the founding congress.

The CPC held its First Congress in Shanghai in July 1921. (Its start was 1 July in official history, although other accounts point to 23 July as the more likely date.) The first session was held at the Po Wen Girls School in the French Concession, later transferring to other venues to evade police action. The final meeting on 31 July was held on a boat in South Lake, in Jiaxing, Zhejiang.

The historic Congress was attended by intellectuals who played leading roles in the May Fourth Movement and were radicalized by it. There were 13 delegates representing over 50 Communists organized into seven branches (six based in cities of China and one in Japan), plus two foreign Communists representing the Comintern. Among the delegates were Li Dazhao, Mao Zedong, Dong Biwu, and Zhang Guotao. Chen Duxiu was elected in absentia as general secretary.

The Congress approved the CPC constitution and discussed the current political situation, the basic tasks of the Party, and organizational issues. It formally laid down the Party’s ideological and political foundation, organizational rules and structure. The CPC stressed the need to organize and educate workers through propaganda work and workers’ schools. It also gave a more definite structure to the party’s relations with various mass organizations, the KMT and other political forces within China, and international formations.

Despite the CPC’s historic leap into existence, its organizational survival was still very tenuous. Its branches were spread too thin. A few dozen Party activists worked full-time, receiving meager allowances, while most other members held salaried jobs.

1.2 Groundwork in Party-building and mass movements

Second and Third Congresses. A year later, in July 1922, the CPC held its Second Congress also in Shanghai. Attended by 12 delegates representing 195 members, it approved the Party’s program for revolution in China. It correctly defined the revolution’s major tasks as the following: to stop the civil war, overthrow the feudal warlords, and build local peace; to reject imperialist subjugation and thus achieve real national freedom for China; and to unite China into a genuine democratic republic. The CPC thus became the first Chinese party to present a program of firm anti-imperialism and anti-feudalism and for a democratic republic.

In June 1923, the CPC Third Congress was held in Guangzhou, this time in an area better secured by the KMT-led Guangdong regime. The 27 voting delegates discussed “The Tasks of the CPC” and united front issues, and elected a nine-member CC which for the first time included Mao Zedong. (Chen Duxiu was reelected general secretary; Qu Qiubai headed the all-important Propaganda Department, and Mao later became secretary of the Organization Department.) In August that same year, the Socialist Youth League held its Second National Congress, also in Guangzhou.

In its first years, CPC membership was still expectedly small although rapidly growing. It more than doubled to 123 members in 1922, and grew nearly 4x (to 432 members) by 1923.

Workers’ movement. The CPC focused mainly on building the workers’ movement—reflecting its fundamental proletarian class character and emulating the experience of pioneer Communist-led movements in industrialized Europe and Russia.

But China’s industries were weakly developed, its proletariat numerically small and unorganized, and workers’ struggles mostly spontaneous. Nevertheless, CPC cadres and members immersed themselves among the masses of workers. Their efforts bore fruit in the rapid advances by the workers’ movement, including unprecedented economic and political mass struggles in the 1921-1923 period.

The newborn CPC set up a Labor Secretariat based in Shanghai in mid-summer 1921, with branch offices in Beijing and other major cities, big mines and railway lines. It also published the Labor Weekly journal (August 1921 – June 1922). Despite brutal suppression, CPC-led labor unions and strikes began to spread in 1921-1922.

In January 1922, the 10,000-strong Chinese Seamen’s Union went on strike in Hong Kong. The strike enjoyed the support of other workers around Hong Kong and Guangzhou, and of Sun Yatsen himself. The strike grew to 100,000, paralyzing Hong Kong for two months until the British capitalists granted substantial wage demands—the Chinese people’s first major victory in a century of anti-colonial struggle.

On 1 May 1922, the National General Labor Union held its first Congress in Guangzhou, representing 100 unions covering up to 300,000 of China’s 1.5 million workers. It was organized by the CPC’s Labor Secretariat, with the support of Sun Yatsen’s KMT and some anarchists—proving the Party’s tremendous progress in labor agitation and organization as well as united front work.

Throughout 1922, some 150,000 workers in more than 100 CPC-led unions launched strikes in major cities and industries, including textile mills, coal mines and railways. But repressive clouds were on the horizon, signalled by the bloody suppression in February 1923 of the Beijing-Hankou Railway strike of 10,000 workers at the hands of a Northern warlord (supposedly a CPC ally) backed by the British.

Initial work in rural areas. As a whole, the CPC during this early period focused on urban work and certain other areas of workers’ concentration (such as railways and mines), and neglected work among the peasantry. However, some Party cadres conducted mass work in rural areas on their own initiative, like Peng Pai who organized peasant unions in Haifeng. Across the country, peasant discontent also took the form of secret societies and spontaneous riots.

1.3 The First United Front (CPC-KMT Cooperation)

In late 1920, Sun Yatsen allied his forces with the friendly Southern warlord Chen Jiongming and his Guangdong Army. On 5 May 1921, he assumed the post of the Emergency President of the Guangdong (Canton) military regime based in Guangzhou and ran it as a revolutionary government.

Sun Yatsen then actively prepared for the Northern expedition—a major military campaign to oust the Northern warlord cliques that ruled most of China. But his government was very unstable. While the Northern warlords fought each other, his ally Chen Jiongming colluded with the Zhili warlords and staged a rebellion against the KMT forces in June 1922. Sun Yatsen was forced to return to Shanghai.

Backdrop: brazen imperialist division of China. In November 1921, the US government invited China, Britain, France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Portugal and Japan to the so-called “Nine-Power Conference” in Washington. The summit reflected the growing struggle between the US and Japan for hegemony in the Far East after World War I.

On 6 February 1922, a nine-power treaty was concluded on the basis of the US-advanced “open door” principle which called for “equal opportunities for all nations in China”. The aim of this treaty was to ensure that the imperialist powers had joint control of China. At same time, it gave extra opportunities for the US imperialists to dominate the field and frustrate Japan’s similar plans of domination.

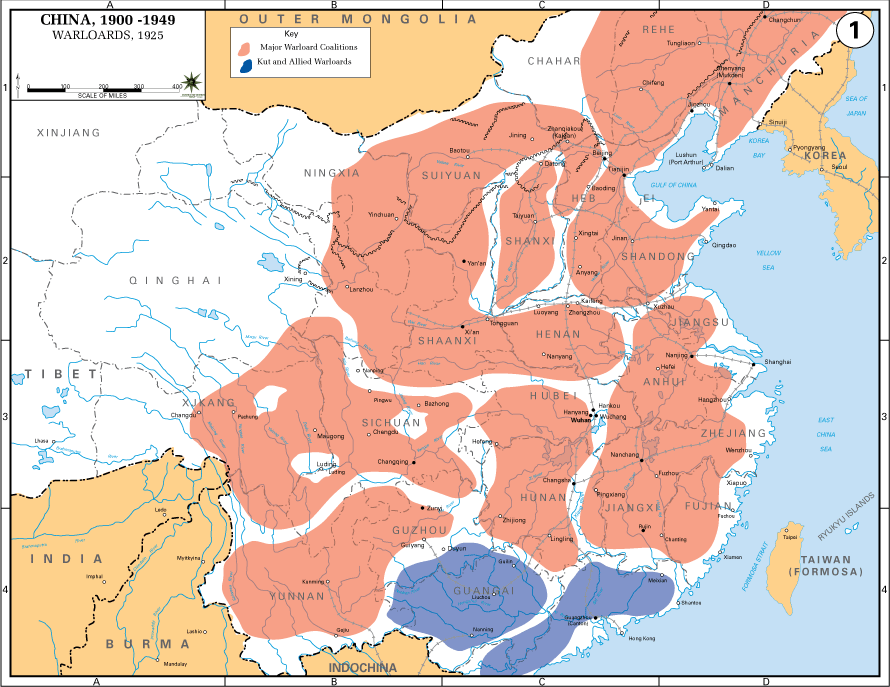

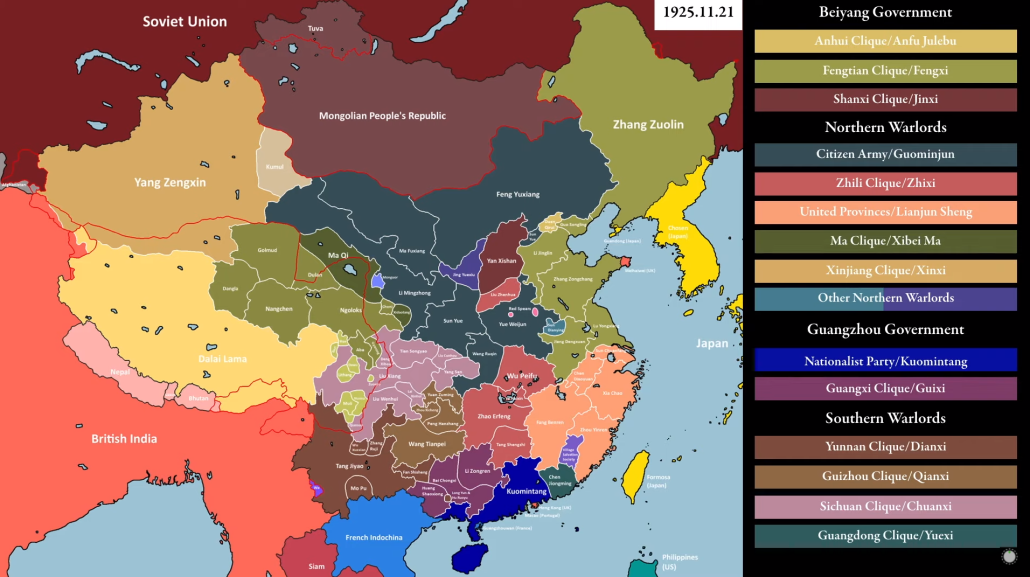

Fig. 1. Map of major Chinese warlord coalitions, 1925

Fig. 2. Detailed map of warlord areas in China, November 1925

Developing CPC-KMT cooperation. Meanwhile, since the August 1922 CC Plenum, key Communists (including Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao) began to enter the KMT, and there were more active efforts to arrange meetings between Sun Yatsen, CPC leaders, and Soviet envoys. (In Europe, Zhou Enlai and Zhu De also joined the KMT to reach and organize the overseas Chinese more widely.)

In Shanghai, Sun Yatsen sought to firm up links with the workers’ movement and the CPC (which had broadened its influence among the workers) as a powerful base for the KMT’s fight against the warlords and imperialists. He also wanted to learn from the Russian revolution and get Soviet support. In January 1923, the KMT Manifesto and the official Accord signed by Sun Yatsen and Soviet envoy Adolph Joffe were issued.

Meanwhile, some southwestern armies allied with the KMT drove out renegade Guangdong warlord Chen Jiongming. Sun Yatsen victoriously returned to Guangzhou in February 1923 and regained his territorial base, this time for good.

Several months later, the CPC decided to formally establish cooperation with the KMT during its Third Congress in Guangzhou. The Party viewed the important role of the KMT and its middle-class base in the revolution. The CPC was to remain independent in ideology, politics and organization, but its individual members were allowed to join the KMT. For its part, the KMT showed its sincere wish to unite with the CPC by allowing this “dual membership” arrangement, although it ruled out a top-level alliance wherein the CPC participated in government as an organized bloc.

In internal CPC discussions, the cooperation with KMT through “dual membership” was also called “united front from within”, as compared to a top-level alliance between two parties or “united front from without.” Communists within the KMT focused on work with the mass movements, and gradually learned to distinguish between the KMT Right, Center, and Left wings and to deal with each trend appropriately.

In January 1924, Sun Yatsen presided over the First KMT National Congress, with Communists such as Li Dazhao and Mao Zedong taking lead roles—signalling the KMT’s dramatic shift to the left. The KMT adopted the Three Great Policies: (1) alliance with Soviet Russia, (2) cooperation with the CPC, and (3) support for the workers’ and peasants’ movements. The Three People’s Principles (nationalism, democracy, and people’s welfare) were further elaborated.

The historic KMT congress proposed a state reorganization based on the principles of decentralization, democratic elections, providing aid to workers and peasants, and state control of big industries away from imperialist control. It called for a unified struggle against the imperialist powers and the feudal warlords.

The KMT’s Guangdong (Canton) regime. From February 1923 onward, Sun Yatsen directly managed military and civil affairs as head of the reestablished KMT-backed regime in Guangdong province, centered on the capital Canton (Guangzhou).

Under Sun’s leadership, the Guangdong regime actively supported the basic movements of workers and peasants, urging the masses of the people to actively participate in political life. In the areas covered by its state power, including parts of Guangxi and Fujian, many demonstrations, marches and public meetings were held to raise the masses’ patriotic and democratic consciousness.

Such measures aimed to mobilize popular support and thus consolidate the KMT base in South China. At the same time, the KMT and its government hoped to develop enough strength to “punish the North”—the bulwark of the powerful warlords that prevented China’s unification under the KMT banner. This gained for the Guangdong regime the sympathy and support of people throughout China while the Northern warlords were steadily exposed and isolated.

With the help of CPC members and Soviet advisers, the KMT and its government machinery were reoriented. Key CPC members took leading posts in important KMT machineries, such as the Organization and Propaganda Departments and the Workers and Peasant Bureaus. Also of strategic importance was the direct involvement of CPC cadres in strengthening the KMT-led Nationalist Revolutionary Army (NRA) and in ensuring its political consolidation.

The Whampoa Military Academy. In a 1921 meeting in Guangxi with Comintern representative Maring (Henk Sneevliet), Sun Yatsen agreed to set up a military academy for NRA officers along the lines of the Soviet military system. Two key CPC leaders worked with the KMT in setting up the academy, while Chiang Kaishek was sent to Russia to obtain arms and observe the Soviet military system. In 1924, the Whampoa (Huangpu) Military Academy was founded in a Guangzhou suburb, with support from the Soviet state.

The Academy’s main goal was to provide basic infantry training, but also provided special courses on heavy weapons, engineering, communication and logistics, and political work. While Chiang Kaishek was its first commandant, key posts for political and military instruction were shared by KMT officials and CPC cadre such as Zhou Enlai and Ye Jianying. Soviet military officers also gave lectures on political-military theory and practice, including those based on recent but rich Soviet experience.

The first two Whampoa graduate batches of 500 officers became the core of the first two regiments of the NRA. The third and fourth batches had 800 and 2,000 officers respectively. Many of these graduates would become Chiang’s base (the so-called “Whampoa clique”) in his rivalry with other KMT factions.

But other graduates would be radicalized and organized by the CPC; after the KMT-CPC break and the 1927 uprisings, they would serve as military commanders of the fledgling Red Army—often facing their Whampoa classmates across the battlefield on the KMT side. (Note: Whampoa graduates would also include future leaders of other Asian national-liberation movements such as in Korea and Vietnam, including Ho Chi Minh.)

Sun Yatsen’s death. In November 1924, already ailing, Sun Yatsen travelled to Beijing to further the cause of China’s revolution and strengthen ties with Soviet Russia as friend and ally. During his visit, he died of cancer on 12 March 1925—leaving a last will that reflected his devotion to the revolutionary cause.

At the same time, Sun Yatsen’s death signalled the gradual rise to dominance of the KMT Right wing, which was becoming alarmed by the gains of the CPC within the Guangdong regime, within the NRA, and within the KMT leadership itself.

2. What were the twists and turns of the First Revolutionary War (1924-27)?

2.1 Main character of the First Revolutionary Civil War

A revolutionary mass upsurge. The First Revolutionary Civil War (1924-27) refers to the revolutionary mass upsurge of workers, peasants, and other patriotic and democratic forces in their struggle vs. the feudal militarists and the foreign imperialists. It particularly refers to the military expedition that waged war against the Northern warlords, and which enjoyed popular support among the masses.

At the same time, by late 1924, worsening economic problems, warlordism, and foreign intrusion all led to a new mass upsurge in the anti-imperialist and anti-warlord movements of 1925-1927, better known as the May Thirtieth Movement. Most students and other petty-bourgeois intellectuals, especially those politicized by the May Fourth Movement, supported the new upsurge of workers’ and peasants’ struggles.

The CPC and KMT jointly and independently waged these struggles against imperialism and warlordism, and gave support to political strikes by workers. CPC-KMT cooperation resulted in bigger gains in the labor movement and in the Guangdong regime’s tax policies. KMT consolidated its political base in South China.

Intensifying warlord rivalries. At the same time, in North China, warlord rivalries intensified. Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin, who headed the Fengtien warlord clique, had defeated Wu Peifu’s Zhili clique in 1924 and became the most powerful warlord in northern China. This resulted in an uneasy alliance between Zhang Zuolin and “Christian general” Feng Yuxiang.

It was in this context that this alliance of Northern warlords invited Sun Yatsen to Beijing for unification talks. But when Sun Yatsen died in March 1925, China’s division into at least six power groups turned for the worse, whipped up by the imperialists and domestic ruling elites.

This was reflected in the intensified struggles within the KMT. Liao Zhongkai (Sun Yatsen’s close comrade within the KMT Left) was assassinated in August 1925. This led Chiang Kaishek (then commandant of Whampoa) to become commander of the NRA. The KMT leadership was divided mainly between the Right-wing led by Chiang and the Left-wing ostensibly led by Wang Jingwei and supported by the CPC.

Bereft of Sun Yatsen’s leadership, but still in the framework of KMT-CPC cooperation, the Guangdong regime continued to complete its political control over much of South-Central China through two Eastern Expeditions and a Southern Expedition in 1924—all successful.

2.2 CPC-led forces, the workers and peasant movements

CPC Fourth Congress. In January 1925, the CPC held its Fourth Congress in Shanghai, with 20 delegates representing about 950 members. Its documents further clarified united-front policies, dwelt thoroughly on the labor movement, touched briefly on the need for agrarian revolution, and discussed errors of Left and Right opportunism. Recognizing the Party’s still narrow membership mostly of intellectuals, it called for more daring recruitment drives among urban and rural workers. (Mao was absent, having returned in late 1924 to his home province Hunan to conduct more focused political work.)

Back-to-back with the CPC congress, the Socialist Youth League also held its Third Congress and changed its name to Communist Youth League (CYL). Within the whole year of 1925, it rapidly expanded from 2,900 to 9,000 members.

The May Thirtieth Movement. Workers’ strikes had been on the rise since early 1925—the most prominent being the strike of 22 Japanese-owned cotton mills in Shanghai and Qingdao—thus breaking the lull on the labor front since the February 1923 massacre of Beijing-Hankou Railway strikers.

In early May, the Second National Labor Congress met in Guangzhou and established the National General Labor Union—claiming 540,000 members in 166 unions, with 218,000 workers in Shanghai alone. On May 15, demonstrations broke out in Shanghai triggered by capitalist violence at the picketlines, and quickly spread to other cities. On May 30, the CPC and other groups called for coordinated mass protests. Later that day, the Shanghai Municipal Police under British command opened fire on protestors, killing 10 and wounding many more, thus further fanning more protests.

The CPC and other groups promptly formed a Shanghai General Labor Union, which rapidly expanded in membership, and declared a general strike on June 1 where students and merchants joined hands with workers. The general strike spread to more than a dozen cities and continued through the next months—despite police repression and divide-and-rule tactics backed by the Shanghai-based foreign powers—winding down only by mid-September.

The high point of the May Thirtieth Movement was the great Hong Kong-Canton strike, which began on June 19. In Canton, British and French troops opened fire at a large demonstration on June 23, killing 52 and wounding more than 100. The masses protested the outrage through a general strike that crippled Hong Kong for 16 straight months, ending in October 1926 only because the KMT asked for breathing space in order to pursue its Northern Expedition.

Dramatic expansion of the Party and mass base. The CPC rightfully claimed that “[from its inception] the Chinese labor movement has been under the direction of our Party.” Throughout 1925, its influence rapidly expanded among the workers, especially among railway workers and seamen.

Other CPC-influenced mass organizations coordinated the upsurge of labor, youth, women, and peasant movements. Great masses of the urban population were roused to new heights of revolutionary energy, inspiring the entire Party to do its best in leading the Chinese revolution.

A direct result of the 1925 revolutionary upsurge was a geometric rise in Party membership: from 1,000 in early 1925 to 10,000 by end-1925 and to around 30,000 by July 1926. Members of working-class origins comprised only 30% in 1925, and rose to almost 54% by early 1927.

The rapid expansion of both Party membership and urban mass organizations required the CPC to also quickly scale up its propaganda-education and training programs, and to expand and reorient its journals and mass newspapers. Guide Weekly, the principal Party journal since 1922, expanded its circulation from 7,000 to 50,000. Party-sponsored bookstores were set up in major cities or provinces as the main outlets for the said materials.

Correspondingly, the CPC leadership gradually built up its central and provincial machineries: organization and propaganda departments in 1921, a Secretariat and women’s department in 1925, labor and peasant departments in 1926, a Military Affairs Committee also in 1926, and regional bureaus and provincial committees in addition to local city committees, branches and cells.

Rapid expansion of peasant mass base. In principle, the CPC had resolved to give more stress to the peasant movement and launch agrarian revolution. In fact, it was the only Chinese political party seriously undertaking peasant work; KMT’s work among the peasantry was also undertaken by Communists inside the KMT, such as Peng Pai and Mao Zedong. However, during the first half of the 1920s, the CPC had only barely begun its peasant work, with Guangdong and Hunan provinces as prominent pioneers.

Through the KMT-CPC cooperation, many peasant associations were set up in Guangdong and Hunan. A Peasant Training Institute was established in 1924. Within two years, the school’s Communist instructors (which included Mao) had trained six batches of cadres for peasant work—each batch numbering hundreds. Peasant struggles grew even more dramatically in terms of extent, intensity and militance. The peasant masses set up local associations and waged agrarian struggles to reduce land rent. They also organized armed militia units to counter the landlords’ militia and at times to attack the warlords.

The peasant associations in Guangdong and Hunan played important roles in the KMT’s projection of its political power to other provinces via the two Eastern Expeditions and the Southern Expedition of 1924, and the Northern Expedition of 1925-26. By mid-1927, the Guangdong peasant associations represented 700,000 members in 73 counties. Hunan’s peasant movement was not far behind and soon surpassed that of Guangdong to become the country’s strongest. On May 1, 1926, peasant associations from 11 provinces held their congress in Guangzhou. By mid-1927, peasant associations throughout China had 9 million members in 16 provinces.

The peasant movement in Hunan. The peasant movement was strongest in Hunan province. By 1927, peasant associations there had a membership of 2 million, and had a mass base reaching 10 million. In four months, the Hunan peasant movement swept through the entire province like a giant storm. This experience was written down by Mao in one of his earliest major works, Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan, published in January 1927.

In that classic work, Mao for the first time laid down the essential role of the peasantry in the Chinese bourgeois-democratic revolution, as its main force and not just as the “direct reserve” of the proletariat as in the Russian revolution. He warmly welcomed the massive revolutionary energies unleashed by the agrarian revolution—which the bourgeoisie and not a few CPC members considered as “excessive” and “terrible”.

But even just the peasant movement’s initial gains already antagonized and alarmed the landed gentry, which had huge influence within the KMT. Many CPC leaders mistakenly viewed this as unnecessarily jeopardizing the united front with KMT; the Party CC’s July 1926 plenum criticized “prevalent left deviations” in the peasant movement. From the start, the Chen Duxiu leadership had belittled the role of the peasantry in favor of the alliance with the middle classes.

2.3 Chiang Kaishek’s rise to power, the Northern warlord threat

The “Canton Coup”. After Sun Yatsen’s death, Chiang Kaishek promptly took the post of KMT generalissimo and, posing as Centrist to hide his Rightist position, began to consolidate his clique’s hold on power.

A naval ship captained by a Communist had maneuvered near Guangzhou on the night of 18/19 March 1926, allegedly to support an imminent Party-led uprising in the area (which the CPC denied). Using this as alibi, Chiang Kaishek promptly declared martial law in the city on 20 March and launched a mass ouster of hardline CPC leaders from the Guangdong government and NRA (the so-called “Canton Coup”).

Mobilizing loyal KMT troops and Whampoa cadets, Chiang had many Communist officers (including Zhou Enlai) arrested and expelled from the army. He also placed Wang Jingwei and Soviet advisors under house arrest. Chiang’s units secured the Communist-commanded ship, pulled out two CPC-influenced garrisons, disarmed the CPC-led Workers’ Guard, and neutralized the Guangzhou-Hong Kong Strike Committee.

The KMT top leadership quickly intervened to avert a total split between Chiang Kaishek and Wang Jingwei, and to preserve Soviet support for the planned Northern Expedition. It ousted or rebuked some Right-wing groups to appease the Left-wing faction, Soviet Russia and the CPC. On the other hand, it also ruled that the CPC should provide a list of all its members working within the KMT, and that Communists would no longer hold top government positions. (Zhou Enlai, ousted from his KMT-NRA posts, moved from Guangzhou to Shanghai to help lead gigantic workers’ struggles there in February-March 1927.)

At the same time, the KMT formalized Chiang’s leadership of the party and army, ending civilian supremacy and paving the way for his exercise of dictatorial powers. Wang Jingwei resigned his posts and went overseas. The uneasy KMT-CPC cooperation teetered on the brink of breakup but remained, and the Northern Expedition proceeded.

The Northern warlords arrayed vs Guangdong regime. The legitimacy of the Beijing-based (Beiyang) government, although recognized by other countries, had a basic flaw. Although nominally upholding the 1911 constitution, it had no parliament and depended on its own warlord coalition—the so-called Fengtian clique. Also, it did not directly control much of China, which was ruled by various other regional and provincial warlords.

Three warlord cliques were opposed to the KMT government in Guangzhou. (1) The forces of Wu Peifu occupied northern Hunan, Hubei, and Henan provinces. (2) The coalition of Sun Chuanfang was in control of Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Anhui and Jiangxi provinces. (3) The strongest coalition, under Zhang Zuolin, head of the Beiyang government and the Fengtian clique, was in control of Manchuria, Shandong and Zhili.

2.4 The Northern Expedition (phase 1)

Start of Northern Expedition. On 1 July 1926, the KMT’s Guangdong regime, in its aim to reunify China in the spirit of the 1911 Revolution and still enjoying Soviet and uneasy CPC support, began the long-awaited Northern Expedition to the Yangtze valley. This was a series of military campaigns focused mainly against the Northern warlords that ruled Jiangxi, Fujian, Hunan, Hubei, Henan, Jiangsu and the Beijing area. Initial victories saw the NRA gaining control of Guangdong and large areas in Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi and Fujian.

On 9 July 1926, with KMT’s blessings, Chiang Kaishek took command of the NRA to stabilize the border between KMT-held territory and that of the Northern warlords. Following Soviet advice, KMT forces first focused on defeating warlord Wu Peifu while keeping Sun Chuanfang neutral.

KMT forces advanced into Wu-controlled Hunan, captured Changsha on 11 July, and took full control of the province on 22 August. On 30 August, the KMT forces (mainly NRA Seventh Army) overran Wu’s forces on their advance to Wuhan (Hubei capital). On 2 September the NRA started the siege on Wuhan, which held out for a month. Most of Wu’s army fled north to Henan, and gradually disintegrated.

Fig. 3. The advances and victories of the Northern Expedition, 1926-27

Next, Chiang’s KMT forces turned to Jiangxi, which was under Sun Chuanfang’s control. By 19 September, they took its two main cities (Jiujiang and Nanchang) but pulled out two days later when Sun’s reinforcements counter-attacked and retook most of the province. This was followed by the brutal killing of hundreds of KMT members and activists.

Meanwhile, the Zhejiang governor defected to the KMT and declared the province’s independence from Sun Chuanfang. But Sun’s forces crushed the rebellion a week later, followed by executions and massacres of thousands of civilians.

KMT forces score series of victories. The NRA continued its offensive in Jiangxi. At the same time, its First Army opened a new offensive into Fujian. Welcomed by the masses, the NRA troops swept across the province and along the coast towards the capital Fuzhou. Sun’s forces retreated across Jiangxi and Fujian. In early November, the NRA reached the Yangtze, and by 9 November retook Nanchang.

Meanwhile, Sun sought aid from the Fengtian clique further up north. Shandong warlord Zhang Zongchang and Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin agreed to give help in exchange for a hefty payment. As the NRA offensive advanced through Fujian, the two warlords reinforced Sun-controlled Anhui on 24 November, and unified all the warlord armies into one “National Pacification Army”.

The Anhui and Zhejiang masses viewed this alliance of warlord armies as unwelcome invaders. In Fujian, many warlord troops defected to the NRA. On 9 December, the NRA First Army entered its capital Fuzhou unopposed. On 11 December, the Zhejiang commander defected to the NRA, triggering more defections and leading to Zhejiang’s shift of allegiance to the KMT’s Guangdong government.

In response, Sun’s army supported by other warlords retook most of Zhejiang by 10 January 1927. To relieve the rebel forces inside Zhejiang, the NRA First Army entered the fray and halted Sun’s advance. The Zhejiang rebels and NRA forces merged and went on a counteroffensive on 20 January.

By end-January, the NRA had defeated Sun’s forces in most of Zhejiang, and took its capital Hangzhou on 17 February. By 23 February, KMT forces completely controlled Zhejiang (except Shanghai), while Sun’s remaining troops fled north to Jiangsu.

KMT expands to seven provinces but internal struggles worsen. In six months, therefore, KMT’s political power had expanded to seven provinces, with a population of about 170 million people. Its NRA had expanded to 700,000 troops, swollen by many defections from warlord armies. But as its authority and military strength grew, internal leadership struggles also intensified.

In January 1927, KMT Left-wing leader Wang Jingwei and his CPC allies moved the seat of the government from Guangzhou to newly liberated Wuhan. A plot-vs-counterplot “tug of war” ensued between the KMT Left-wing and Chiang (who posed as Centrist but was in fact Right-wing).

Shanghai-Nanjing offensive (February–April 1927). The defeated warlord Sun Chuanfang’s forces retreated to Nanjing. The Fengtian clique aided him by reinforcing Jiangsu and Anhui, and Henan as well in support of the other defeated warlord Wu Peifu. Two major Fengtian armies (the Shandong Army of Zhang Zongchang and the Zhili Army of Chu Yupu) crossed the Yangtze River in February 1927 to help Sun defend Nanjing and Shanghai, which were now threatened by the Hangzhou-based eastern NRA.

The NRA launched a two-pronged attack on those two cities in mid-March. One column advanced toward Shanghai, while another moved toward Changzhou to cut off Sun’s access to the Shanghai-Nanjing railway.

Meanwhile, aided by more defections among Sun’s forces, Cheng Qian’s central NRA advanced through Anhui toward Nanjing. The remnants of Sun’s forces, aided by the Shandong Army, retreated to Shanghai proper. Sun’s forces were further beset by NRA forces cutting his railway links to Nanjing and the defection of his navy units.

Shanghai falls to allied KMT-CPC forces. At the same time, on 21-22 March within Shanghai itself, allied KMT-CPC forces led by Zhou Enlai and Chen Duxiu and based on a powerful workers’ general strike launched an armed uprising against Sun’s forces in support of the advancing NRA units. Even before the NRA’s Eastern Route Army arrived, the CPC-led workers’ militia overwhelmed Sun’s forces and set up political power throughout the city except in the international settlements.

After intense fighting on 22 March, NRA forces marched victorious into Shanghai. The NRA generals ordered a halt to the CPC-led general strike, while the remnant armies of the Northern warlords fled across the Yangtze back to their bulwarks.

As the first phase of the Northern Expedition drew to a close, the NRA scored more victories in Anhui, capturing its capital Hefei. NRA forces north of the Yangtze reached northern Jiangsu but stalled due to the Nanjing Incident and rising tensions between the KMT Left in Wuhan and the KMT Right in Nanjing. At the same time, the Northern warlords eventually regrouped for a new counteroffensive on 3 April and pushed the NRA forces back to the Yangtze by 11 April.

3. How did the KMT-CPC alliance end with the 1927 anti-communist coup?

Alarmed by the nationwide revolutionary upsurge, the imperialists and the domestic big bourgeoisie set out to assert their control over the KMT and to break up the KMT-CPC alliance. The anti-communist alarm spread among the high-ranking NRA officers, who came mostly from wealthy families and shared (or aspired for) big-comprador-landlord class interests.

There were already differing class alignments within the KMT from the start, and the cracks widened into fissures especially when Sun Yatsen died in 1925. The KMT Left continued to support Sun’s Three Great Policies of aligning with Russia, the CPC, and the workers and peasants. The KMT Right opposed the Three Great Policies, represented big comprador-landlord class interests, and was backed by the imperialists.

Led by Chiang Kaishek, the Right deftly maneuvred to seize control of the KMT and NRA. The Chiang clique edged out the Left, still nominally headed by the wavering Wang Jingwei but in reality now led by Soong Ching-ling (Sun Yatsen’s widow).

3.1 The Nanjing Incident and growing KMT-CPC tensions

In early 1927, the Northern Expeditionary forces had reached the Yangtze region while the Northern warlords’ armies suffered massive defections to the South. With the Northern warlords having weakened and some crossing over to Chiang’s side, the KMT Right decided to shift its main focus of attack on the CPC and its mass base.

After taking Shanghai, the forces of the Northern Expedition targetted Nanjing next. The warlord-led Shandong Army withdrew on 23 March 1927, and NRA forces entered the city with no resistance. Almost immediately, anti-imperialist mass protests broke out in Nanjing, and its foreign concessions were attacked and looted. British and US ships evacuated their citizens and bombarded the city, leaving it scorched and killing at least 40. More NRA forces arrived on 25 March and eventually restored order.

This was later to be called the Nanjing Incident. Egged by foreign powers, Chiang and KMT Right-wing elders blamed the Nanjing Incident on the KMT Left and the CPC. The KMT Left-dominated civilian government—now based in Wuhan—was growing more radicalized. Chiang now clearly viewed the CPC and the KMT Left leaders as obstacles to his own NRA-based authority.

The Right wing pushed the KMT leaders to officially delink from the CPC. For its part, the CPC leaders knew that Chiang was preparing fot an anti-communist coup, but estimated that the mass movement’s pressure could still prevent or blunt it. Hence CPC-led organizations launched intense mass struggles in Wuhan and elsewhere in KMT-controlled territories.

In Shanghai itself, CPC’s forces rapidly grew in strength and organized daily mass protests by students and workers’ strikes—particularly to demand the return of Shanghai international settlements to Chinese control. It provided militia training and hidden arms to 2,700 workers. Taking advantage of its influence within NRA units in the field, it created parallel organs of political power in areas newly liberated from warlord control.

But Chiang was tightening his hold on the NRA, which in turn was tightening its hold on Shanghai. The Right focused on consolidating its hold on the entire KMT and purging it of CPC influence. On 2 April the top KMT leadership condemned the CPC actions in Nanjing and voted unanimously to purge the KMT of all CPC members. Anti-communist crackdowns had already started in Hangzhou and Fuzhou.

Wang Jingwei tried to counter Chiang’s anti-communist moves. Meeting with CPC leaders in Shanghai on 5 April, he and Chen Duxiu reaffirmed KMT-CPC cooperation. The CPC leaders, still pinning their hopes on saving the ruptured united front, decided not to initiate the break and continued to support Wang’s KMT Left. Once Wang returned to Wuhan, Chiang made his move.

3.2 Anti-Communist coup and bloodbath

On 9 April, Chiang declared martial law in Shanghai, while KMT elders denounced the Wuhan government’s policy of KMT-CPC cooperation. On 11 April, Chiang ordered all provinces under his control to oust all CPC members from the KMT. The notorious Green Gang and other pro-Chiang underworld groups attacked the General Labor Union’s Shanghai offices.

Finally, in a pre-dawn crackdown on 12 April, the NRA’s 26th Army and its Green Gang thugs struck against workers’ strongholds and disarmed the workers’ militias in Shanghai, Nanjing and elsewhere. In the ensuing firefights in Shanghai, more than 300 people were killed and wounded. Many radical leaders (including Zhou Enlai) were rounded up. On 13 April in Shanghai, 50,000 protesting workers and students marched against a division HQ of the 26th Army. NRA troops opened fire, killing 100 protestors and wounding many more.

Chiang dissolved Shanghai’s CPC-influenced provisional government. He banned all unions and other organizations under CPC control, replacing them with those loyal to the KMT. At least 1,000 CPC members were arrested, 300 executed, and over 5,000 went missing. Other sources estimate higher numbers of Communists killed—from 5,000 to 10,000. On 15 April in Guangzhou, the NRA arrested 2,000 and killed over 100 CPC members and mass activists.

Fig. 4. CPC-led workers’ militia occupy Shanghai (March 1927) on the eve of Chiang Kaishek’s bloody coup

On 18 April, Chiang’s KMT faction set up its own government in Nanjing, with him as head. The Nanjing government was largely supported by the imperialists and local ruling classes, and also by most of the NRA’s top officer corps (who belonged to the landed gentry). The Wuhan-based KMT Left—with 39 members of the KMT Central Committee as signatories, including Soong Ching-ling (Madame Sun)—denounced Chiang’s actions as a treacherous power grab.

The CPC’s urban-based leadership went underground or fled to safer sanctuaries to escape the bloodbath in Shanghai, Nanjing, Guangzhou and elsewhere. Most Party leaders made their way to Wuhan and established a new center in Hankow (one of the three Wuhan cities). Calls echoed for the Party to raise its own army of workers and peasants. Many NRA officers who were radicalized at Whampoa and sympathized with the workers and peasants quietly held on to their field units, awaiting for an opportune moment to respond to the CPC’s calls.

Meanwhile, the gigantic anti-communist deluge rampaged across China. The CPC and its militant mass organizations, especially workers’ unions and the Young Communist League (YCL), were attacked and declared illegal. CPC members and mass activists were rounded up by the thousands and murdered. The workers’ movement and its party were greatly weakened by the brutal rampage.

3.3 CPC Fifth Congress

Amidst the crisis, the CPC held its Fifth National Congress in a Hankow elementary school from 27 April through the first week of May 1927. Some 80 delegates attended, representing nearly 58,000 Party members. The YCL’s Fourth National Congress followed shortly on 10 May, with a base of 35,000 members and 120,000 Young Pioneers (under 15 years old).

The Fifth Congress elected a 29-member CC (with 11 alternates) who in turn elected a Political Bureau of nine, including Chen Duxiu (also general secretary), Zhang Guotao, Li Weihan (Lo Mai), Cai Hesen, Qu Qiupai, Zhou Enlai (also head of the Military Affairs Committee or MAC), Li Lisan, Tan Pingshan, and Su Chao-cheng.

The Fifth Congress focused on the most urgent questions of the day, particularly on the united front, military work, and on the mass movements including the agrarian revolution. Chen Duxiu’s right opportunism and capitulationism was criticized, as well as the policy of unprincipled concessions (not just by Chen but also as advised by the Comintern) to maintain the KMT-CPC united front at all costs.

The CPC asserted that the class united front led by the proletariat and inclusive of the peasantry and urban petty-bourgeoisie remained as a current goal, despite the treachery of the KMT Right representing the ruling classes and the vacillation of the KMT Left representing the national bourgeoisie.

(The Wuhan government, still existing at that point, had recently decided to send forces to continue fighting the Northern warlords and drive up to Beijing. The CPC congress decided to support this initiative while taking care not to weaken its mass base in the south.)

Finally, the Congress adopted an agrarian program—reflecting the heightened militancy of peasant struggles—that applied the confiscation policy to all landlord properties but excluded small landholdings and those owned by the families of revolutionaries. It set a fairly high maximum retention size of farmland as a united front consideration.

3.4 KMT-CPC cooperation ends, Wuhan government crumbles

The dual power of two rival KMT governments (Chiang’s Right-wing KMT in Nanjing, Wang’s Left-wing KMT in Wuhan) lasted less than two months.

In May 1927, NRA troops repeatedly attacked Wuhan-area CPC leaders and activists. Within 20 days, they arrested and summarily executed more than 10,000 CPC members and activists in many cities and towns across China. In Hunan, for example, NRA generals formerly loyal to the leftist Wuhan regime defected to Chiang’s side on 21 May, broke up the peasant unions, hunted down the provincial CPC leaders (including Mao as provincial Party secretary), and killed several hundred Party members and peasant activists in what is now known as the “Horse Day Massacre.”

But the CPC leadership wavered in breaking ties with the increasingly reactionary KMT and in actively fighting the NRA’s brutal onslaught. For example, it had earlier approved, then called off, the plan of its Hunan forces to lead some 300,000 peasants to march on Changsha on 31 May to retaliate for the Horse Day massacre.

Finally, on 13 July 1927, the CPC broke all official ties with the KMT and recalled all its representatives from their KMT posts. CPC leaders still in the Wuhan area went underground and dispersed to various provinces. In the midst of the anti-Communist butchery, Chen Duxiu resigned his post as CPC general secretary on 15 July and was replaced by Qu Qiubai.

The Wuhan government, now bereft of mass support, quickly crumbled. Wang Jingwei, who had long been wavering, fully broke with his CPC allies, reconciled with Chiang, and fled to temporary safety in Europe. Now that Chiang was clearly KMT’s sole undisputed leader, the Soviet Union officially broke up with it. Soong Ching-ling joined Soviet advisors on their train journey back to Moscow.

3.5 Factors that led to the revolution’s 1927 setback

China’s bourgeois-democratic revolution that started in Guangdong, in Mao’s words, “had gone only halfway when the comprador and landlord classes usurped the leadership and immediately shifted it on to the road of counter-revolution.”

Objective conditions enhanced subjective weaknesses. The treachery of Chiang Kaishek and the KMT Right-wing provided the immediate objective conditions that led to the revolution’s major but temporary setbacks. But subjective weaknesses were more decisive during this period, especially the erroneous lines and policies pushed by the CPC leadership in the 1921-27 period, prior to Chiang’s anti-communist coup. In this period, conditions were ripe for many errors to prevail within the newly established Party, which was still small, too young and inexperienced.

In the early and middle phases of this period, the CPC’s general line was correct. The overwhelming majority of its cadres and members were dedicated to the revolution. This was why the Party was able to take root among the workers and (initially) peasants, survive the first attcks, and recover later despite the many setbacks. Nevertheless, the very young Party understood only vaguely the three weapons of the revolution—Party building, armed struggle, and united front. It did not have sufficient understanding of Chinese history and society, and the specific characteristics and laws of motion of the Chinese revolution—which were important in combining Marxist-Leninist theory and the practice of the Chinese new-democratic revolution.

The bulk of the CPC’s small and weak forces during this period was concentrated in major cities such as Guangzhou, Shanghai and Wuhan—which were also the main political, military, economic and cultural base of the imperialists and Chinese big bourgeoisie. With only the successful Russian revolution to draw lessons from, and with the CPC’s initial forces drawn from the mostly-urban proletariat and petty bourgeoisie, it only had a vague idea of the enormous objective differences between Russia and China in terms of shaping revolutionary strategy and the role of the peasantry and agrarian revolution in the vast countryside.

For this reason, towards the latter phase of this stage, the CPC’s leading cadres failed to define the correct strategic path for consolidating its gains. They fell for the deceptions of the bourgeoisie that had come to dominate the KMT, and brought the revolution to failures. (For details, read Mao Zedong’s “Introducing The Communist”, SW vol. 2)

Right opportunist line. The CPC’s first leadership, as represented by Chen Duxiu, pushed a Right opportunist political line that pursued unity without struggle, in its over-obsession with a united front with KMT. Despite the growing signs of counter-revolution and Chiang’s impending coup, and despite increasing calls from other Party leaders (including Mao) to shift tactics, Chen Duxiu stubbornly persisted in KMT-CPC cooperation.

The two-line struggle between Right opportunism (as represented by Chen) and other Party leaders pushing for urgent course correction was the first in CPC history. It pertained to how the proletariat exercised leadership in China’s revolution. While the CPC correctly characterized this revolution as bourgeois-democratic, Chen insisted that the proletariat should give way to the bourgeoisie—as represented by the KMT—in leading the revolution.

At the same time, this Right opportunist line grossly belittled the strategic value of building the worker-peasant alliance. It over-emphasized the value of urban work and the conduct of the practical workers’ movement. Meanwhile, the Party neglected rural work and the peasant movement. It also imposed excessive restraint on the agrarian revolution’s demands and methods—an error which Mao roundly criticized in his renowned report on the Hunan peasant movement. ■

Forthcoming: Part 3 and 4 – Emergence and development of the Red Army and Red areas, and the Long March (1927-1936)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!