Primer on China’s Revolution and Maoism, Part 3

This is Part 3 of the PRISM Primer on China’s Revolution and Maoism, drafted in 2021 on the occasion of the centennial anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China (CPC). The study material is offered to all socialists and anti-imperialist and democratic activists, and will be posted in 10 parts.

PRIMER ON CHINA’S REVOLUTION AND MAOISM

On the occasion of the 100th year of the Communist Party of China

Prepared by Andi Belisario for PRISM (Reissued 1 October 2022)

(Part 3. Emergence and development of the Red Army and Red Areas)

III. EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE RED ARMY AND RED AREAS (1927-34)

China’s Second Revolutionary Civil War (also known as the Revolutionary Agrarian War) began in 1927 and ended essentially when the Long March reached North China, where the CPC and its Red Army established headquarters in Yanan in 1936. For this primer’s purposes, this period of intense revolutionary struggles will be treated in two parts. Part 3 will focus on the emergence and development of the Red Army and Red Areas prior to the Long March.

1. How did the armed uprisings of 1927 lead to the emergence of the Red Army?

1.1 The armed uprisings of 1927

Nanchang and Hailufeng uprisings. In response to the Chiang Kaishek regime’s massive anti-Communist onslaught and the breakup of the united front with the KMT (see this primer’s Part 2), the CPC shifted to a policy of armed uprisings. The new provisional Party center led by Qu Qiubai decided to take the momentous decision of creating a Red Army and to seriously plan for insurrection and related military actions. Uprisings were projected for Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi and Guangdong, supported by mutinies within Communist-influenced units of the KMT-led National Revolutionary Army (NRA).

The CPC’s influence was strongest in the NRA’s Fourth Army, which had returned to Wuhan in July 1927 after its Henan campaign against Northern warlords. Many future top commanders of the CPC-led Red Army were in key Fourth Army posts. These included He Long, Ye Ting, Zhu De, Chen Yi, Nie Rongzhen, Ye Jianying, Liu Bocheng, and Lin Biao.

The Fourth Army now moved east to northern Jiangxi to block Chiang’s further advance. Zhou Enlai and many other CPC leaders had gathered in the vicinity of Nanchang (capital of Jiangxi). They decided that conditions were ripe for local uprisings, and set up an ad hoc Nanchang Front Committee to serve as the insurrection’s command center. (Even before this, Party units in Guangdong’s Hailufeng area—buoyed up by a militant peasant movement—had already initiated local uprisings.)

On 1 August 1927, a 30,000-strong force of the NRA Fourth Army, under strong CPC influence and led by He Long, Ye Ting, Zhou Enlai, Zhu De, Ye Jianying, Liu Bocheng, Nie Rongzhen, and Lin Biao, launched the very first centrally planned uprising against the KMT’s anti-communist onslaught. (The rebel forces, organized into nine divisions, later formed the core of the Second Front Army.) After a four-hour attack on Nanchang, they took the city together with some 5,000 firearms and stocks of ammunition.

By 5 August, however, the Nanchang rebel forces had to retreat in the face of counter-attacks by a vastly superior KMT force. In what is now known as the 500-km “Little Long March,” the retreating rebels circled through Guangxi and western Fujian, then to Shantou in September. One group led by He Long and Ye Ting linked up with the Hailufeng rebel forces led by Peng Pai in October and waged guerrilla warfare in that area. Another group led by Zhu De fell back to Hunan province and linked with Mao’s forces in early 1928.

Although both failed, the Nanchang and Hailufeng uprisings played an historic role as the signal fire of revolutionary people’s war against the KMT reactionaries. The NRA units that joined the uprisings, in resisting the KMT counter-revolution, thereby declared their revolutionary stand to fight for the workers and peasants. August 1 has been celebrated since then as the birthdate of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

On 7 August 1927, an Emergency Conference held in a Wuhan suburb chose a new provisional nine-member Politburo headed by Qu Qiubai. (Mao was among the PB’s alternate members). The CPC resolved to bolster its regional centers of leadership, streamline its disorganized rank-and-file, and tighten its underground networks and methods. The Young Communist League (YCL) also met in Wuhan on 12 August to realign its work along the new urgent tasks.

The CPC criticized itself for neglecting work among the peasant masses, adopted more militant agrarian policies and plans for rural insurrection—including preparations for a general peasant insurrection in time for the forthcoming autumn harvest.

Autumn Harvest uprisings. The CPC leadership was still pushing for armed action mostly among the urban workers. But since the KMT overwhelmingly controlled the cities, while peasant struggles raged in the countryside, the Party increasingly realized the urgent need to mobilize its rural forces and wage agrarian revolution—especially upon the urging of other leading cadres like Mao.

The CPC thus decided to launch armed uprisings mainly in Hunan and Hubei, and parts of Henan and Anhui, where the peasants were organized and armed. Hundreds of mine workers from nearby Jiangxi were also ready to join. The second wave of uprisings, now known as the Autumn Harvest uprisings, began on 8-9 September 1927. (The uprising in Hunan was under Mao’s direct leadership.) The immediate goal was to “overthrow the Wuhan regime and establish a genuine revolutionary government of the common people.”

The uprisings broke out simultaneously around Changsha and Liling (key Hunan towns), and some Hubei counties. The Red forces set up local Soviets (organs of political power) in the areas they controlled, but could not defend these against the much stronger KMT forces. By 17 September, only less than half of the Red forces remained. Numbering about 1,000 and led by Mao, they retreated to the Jinggang mountains along the Hunan-Jiangxi border.

Other uprisings. For historical accuracy, it must be noted that CPC forces and local peasant organizations had already seized Haifeng (in Guangdong) for a week, as early as May Day 1927, before retreating. Later on 17-25 September they seized nearby Lufeng and retook Haifeng, declaring—for the first time in Chinese history however shortlived—a “worker-peasant dictatorship” in the area. Then they retook the Hailufeng area once more on 7 November 1927 and excercised local Red political power for nearly four months.

In that same autumn, there were also lesser uprisings in other counties of Guangdong, Hunan, Hubei, and Hebei, followed by still others in early 1928 in Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Hebei, Henan, Shaanxi and elsewhere. In late October and early November 1927, warfare also broke out between the KMT-Chiang’s Nanjing government and the dissident warlord General Tang Shengzhi in Wuhan. Tang’s forces were defeated on 9 November. The CPC’s Hubei Committee led a half-baked uprising on 13 November but this too was quickly suppressed.

1.2 Continued pursuit of the urban-insurrectionist line

PB meeting remains obsessed with city insurrections. A special enlarged Politburo (PB) meeting on 9-10 November 1927, under Qu Qiubai’s leadership, approved markedly ultra-Left policies. Although it abandoned the policy of united front with the KMT, its main focus remained on armed uprisings in the big cities among workers, while belittling the revolutionary potential of the peasantry.

Qu Qiubai confused the concept of “continuous revolution,” in asserting that the Chinese revolution was in a condition of “permanent flow.” In effect, he blurred the difference between the democratic and socialist revolutions. This line did not distinguish between the national bourgeoisie and the comprador big bourgeoisie, and conflated their interests as a single class enemy. It pushed other subjectivist and ultra-Leftist presumptions that over-estimated the objective situation and the capacity of CPC’s forces.

The Qu Qiubai leadership grew obsessed and impatient with winning urban insurrections, and viewed guerrilla warfare and rural bases as just a set of tactics to hasten urban victory. It used this framework as basis for criticizing various errors and shortcomings. It viewed the failed uprisings as due to “serious mistakes” in tactics (basically, that the Party cadres did not exert enough efforts to mobilize the masses) instead of making a more balanced assessment between the strategic error of persisting in urban insurrections, on one hand, and strategic gains in creating the Red Army and retreating to the rural areas to build Red bases on the other hand.

The CPC leadership’s wrong analysis and line—which disregarded the revolution’s current stage, the enemy’s strength and the masses’ level of consciousness and fighting capacity—proved disastrous. Based on this ultra-Left line, relatively small and weak groups of Party members and mass activists were made to launch local urban uprisings throughout China despite the absence of many factors for victory. The series of uprisings in 1927 failed, proving the line’s bankruptcy.

Guangzhou uprising (“Canton Commune”). The Qu Qiubai leadership gave too much weight to the conflict between NRA’s Zhang Fakui (Fourth Army commanding general who remained loyal to the Wuhan regime and had many communist junior officers), on one hand, and Chiang Kaishek’s own clique of NRA warlord-generals on the other hand. When Zhang’s forces occupied Guangzhou in a coup on 17 November 1927, creating a temporary power vacuum, the CPC leadership seized on the opportunity for a third major uprising, despite very slim chances of success.

On 11 December 1927, CPC-led armed units—mostly a Party-led cadet regiment of 1,200 and a hastily created 2,000-strong workers’ militia (“Red Guards”)—occupied Guangzhou and proclaimed a Soviet government. All political prisoners were freed, most capitalist property were deemed nationalized, wage increases and an 8-hour day were declared, and debts canceled.

Many unfavorable conditions worked to hinder mass support for the Guangzhou uprising. Zhang’s NRA units, which were five times bigger than the rebel units, remained loyal to the KMT. Supported by the imperialists, businessmen and yellow unions, the KMT forces (six divisions) promptly attacked and defeated the armed uprising two days later.

Thus, the “Canton Commune” lost its mass character, quickly turned defensive, and soon collapsed. Its defeat led to a more horrific wave of anti-communist rampage, in which 5,700 Communists, worker activists and other progressive people were dragged out and killed in public. Many others were arrested, tortured, and executed or given long jail sentences. Some 1,500 CPC members and mass activists escaped to Hong Kong or Hailufeng.

Lessons on premature urban insurrections. The Qu Qiubai leadership, in further pushing its ultra-Left line, led to a big number of setbacks and gradually came under criticism from other leading cadres such as Mao. Qu Qiubai’s wrong line dominated the CPC until April 1928.

Mao would later draw lessons from the 1927 uprisings. He concluded that the revolutionary movement must not undertake premature urban insurrections and the Red Army must not attack the cities, where the enemy was strongest. Rather, the Red Army must concentrate its efforts in the rural areas where the enemy was weakest and, with the support of the peasantry and agrarian revolution, guerrilla warfare and base areas could be sustained for long periods. The first efforts in rural work, while failures per se, bore fruit in the following years in the form of the first Red areas in the history of China and other countries outside of Soviet Russia.

The series of attempts at urban insurrection in 1927 served as the transition period from the mainly urban-based struggles in 1921-27 to the peasant-based armed struggles from 1927 onwards. In this next stage of the revolution, the CPC-led forces were able to build their own Red Army and exercise Red political power through armed struggle, agrarian revolution, and by developing rural bases mainly among the peasantry.

2. How did the Red Army start building political power in the Red areas?

It was in China where a proletarian party established the first revolutionary base areas (also called Red Areas or Liberated Areas) where it exercised and gradually expanded political power long before nationwide victory. This was an unprecedented achievement of the world proletarian revolution after the Paris Commune and the 1917 Russian revolution.

It proved once more that, given the uneven development of capitalism and the weak links in the global chain of imperialism, it was possible for the proletariat and its class allies to win and further develop Red political power in certain areas (such as rural areas, if not yet an entire country) where the revolutionary situation was ripe and where the enemy was weakest.

2.1 The first Red areas

Jinggangshan and the Hunan-Jiangxi border area. By October 1927, the small ragtag Red Army led by Mao advanced further into the Jinggang mountains (Jinggangshan)—a sparsely populated and thickly wooded masiff about 100 km long by 30 km wide (with 1500 m elevations) in the isolated border region between Hunan and Jiangxi.

In what is now famously known as the Sanwan Reorganization, (https://peopleshistoryofideas.com/episode-62-entering-the-jinggangshan-the-sanwan-reorganization-of-the-peoples-army/), Mao used persuasive methods to institute democratic reforms and consolidate the ragtag army. His forces also struck an alliance with two former bandit groups entrenched in the area, then gradually absorbed their forces as it settled down to establish guerrilla bases in favorable mountainous territory.

Under Mao’s direct leadership, the Red Army honed its principles and practical capacity in actual guerrilla war, “learning warfare through warfare.” In November 1927, by adopting an excellent combination of political and military policies and after scoring a number of tactical victories in battle, the Red forces regained enough strength to proclaim a Worker-Peasant Revolutionary Government in the Hunan-Jiangxi border area.

Zhu De’s forces (also regimental strength) had retreated from the Nanchang uprising in September 1927 to another besieged base in northeast Guangdong. In end-1927, Zhu De’s forces moved west to the Hunan-Jiangxi border to seek out Mao’s more stable rural base rather than be decimated again in the Canton Commune as ordered by the ultra-Left CPC leadership under Qu Qiubai. In April 1928 his forces arrived in Jinggangshan and linked up with Mao’s forces.

Building the Party and Red Army. Within the Red area, Party committees were set up at the county level, below which were the local district committees and branches. Government affairs were handled through local Party-influenced worker-peasant-soldier “people’s committees.” On 20 May 1928, the Hunan-Jiangxi Border Area held its first Party Congress, and (among other decisions) upheld the institution of soldiers’ committees to ensure full democracy within the Red Army.

On 1 August 1928, the first anniversary of the Nanchang uprising, the four regiments led by Mao and Zhu De (as Party representative and commander in chief, respectively) were designated as the Fourth Red Army. (Later, this formidable force would be redesignated as the I Corps, and still later form the core of the First Front Army.)

One out of four Red fighters was a Party member. At the Red Army’s Kutien Conference in December 1929, Mao delivered his now famous “On Correcting Mistaken Ideas within the Party.” Later, widespread ideological education within the Red Army included the “Three Rules of Discipline and Eight Points for Attention” (the famous “3/8”) and the mass line principle in organizing the people and leading their struggles. Party activists in the Red Army and in the localities led in setting up village militia (Red Guards), as well as youth and women’s organizations.

Other rural Red areas. By 1929 Mao’s and Zhu’s forces broke through the KMT blockade, doubled to 4,000 and had expanded to the more populated areas of south and east Jiangxi and west Fujian, while a 1,000-strong force led by Peng Dehuai remained in Jinggangshan. The CPC declared this new and larger base area as the Jiangxi Soviet, with the town of Ruijin as its headquarters. By 1931-32, this Red area would become the Central Soviet, and serve as the main base of the Chinese armed revolution until the start of the Long March.

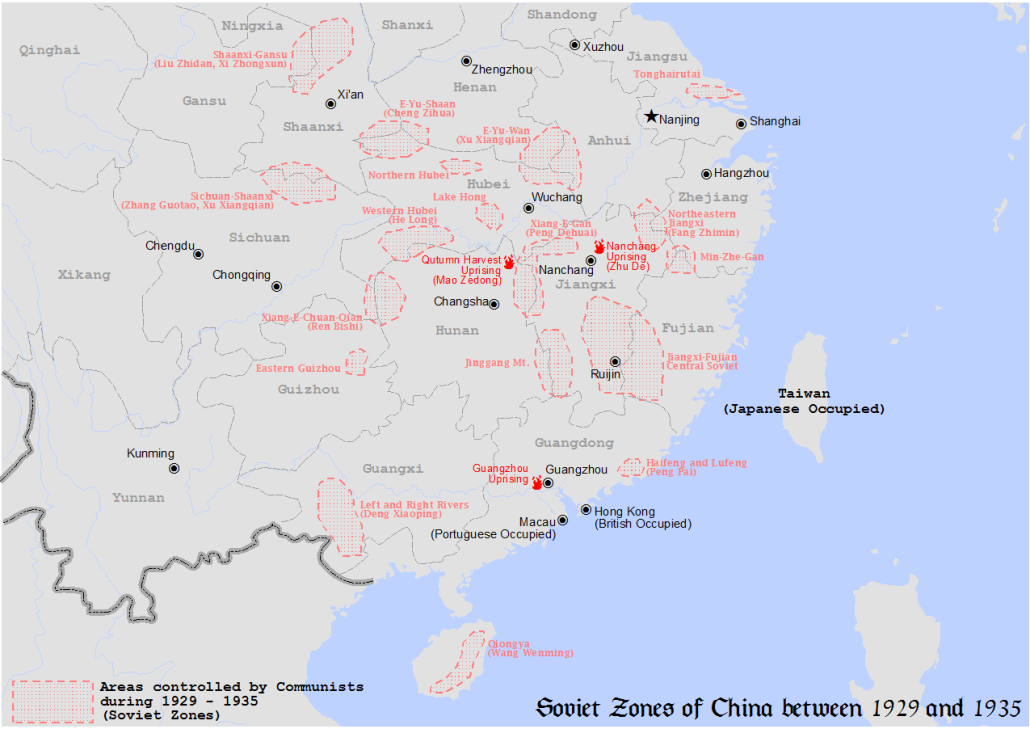

CPC history has rightfully registered the Jinggangshan as the location of the very first base area of the Chinese revolution. Nonetheless, in the 1928-29 period, more rural bases with their own Red armies emerged in quick succession in several other provinces where the CPC’s armed insurrectionary forces retreated and continued to operate. By end-1929, some 15 such base areas existed in seven provinces of Central and South China. The Red Armies, organized into four corps, rapidly grew in size from less than 10,000 in 1928, to 22,000 in 1929, and to at least 60,000 (or 20 infantry divisions) in April 1930.

In northeast Jiangxi, Fang Zhimin established a county-sized rural base from May 1928 onwards. In northwest Hunan and southwest Hubei, He Long and Zhou Yizhun joined forces in early 1928 to build another rural base, operating on both sides of the Yangtze with a 3,000-strong Red Army. Also in the spring of 1928, a separate 1,000-strong Red Army led by Xu Xiangqian and Xu Haidong operated in the Dabie Mountains and built the foundations of the famed Eyuwan Soviet in the Hubei-Henan-Anhui border area. These were just the earliest and major rural bases. Many others emerged and proliferated across China, and exerted a combined nationwide impact in the following years (1930-34) before the Long March.

It was in the context of this nationwide development of rural bases that Mao wrote “Why Red Political Power Can Exist in China?” (October 1928) and shared the earliest lessons of rural base-building in his “The Struggle in the Chingkang Mountains” (November 1928).

2.2 CPC membership, Sixth Congress, and ultra-Leftism

From a peak of 58,000 in April 1927, the CPC’s membership plummeted to less than 12,000 by year’s end due to casualties and dispersals during Chiang’s treacherous anti-communist rampage. Then it bounced back to 40,000 by mid-1928 and to 100,000 later that year—fuelled by its direct leadership of Red armies and rural base areas where it exercised Red political power—although Party strength remained very fluid and fluctuated wildly due to the political-military situation. Members of peasant origin became the majority.

By the early 1930’s, the CPC could once more boast of maintaining at least 10% of its members in deep underground networks in the so-called White areas. These were the urban areas and many rural areas not yet covered by the Red bases. Nevertheless, Party members of working-class origin fell from more than 50% in 1927 to less than 8% in 1930.

CPC Sixth Congress. The CPC’s Sixth Congress was held in Moscow from 18 June to 10 July 1928, attended by 84 regular delegates and 34 alternates representing 40,000 Party members within China and overseas. The Congress characterized Chinese society as semicolonial and semifeudal, and the Chinese revolution as a bourgeois-democratic revolution.

The Sixth Congress drew lessons from the failed KMT-CPC alliance and subsequent uprisings. It severely criticized Chen Duxiu’s leadership and Right opportunist policies. At the same time, it criticized putschism, military adventurism and commandism—which isolated the Party from the masses—as the most dangerous internal tendencies.

On the other hand, the Congress failed to fully understand the dual character of the middle classes and internal contradictions among the reactionaries, and to apply appropriate policies. Also, it only barely grasped the long-term character of the democratic revolution, and the strategic need at that particular period (1927-29) for a planned and orderly retreat from urban to rural areas.

At that time, the Maoist strategy of protracted people’s war had not yet taken shape. Rather, the Congress analyzed the situation as a “lull between two revolutionary high tides,” and set the Party’s tasks in the more familiar framework of the Russian revolution. Recognizing that the Chinese revolution was developing unevenly, the CPC set “winning over the masses to the side of revolution” as its general task. But its specific tasks remained geared towards offensives and uprisings in the urban areas.

The new leadership elected by the CPC Sixth Congress reflected the ambiguous unity in strategy and tactics. Qu Qiubai officially replaced Chen Duxiu, but did not change the strategic policies.

3. How did ultra-Leftism continue to undermine the gains of the Red Army and Red Areas?

3.1 Li Lisan’s ultra-Leftism and the 1930 uprising

Despite the Sixth CPC Congress criticism of ultra-Left tendencies in 1927-28, the new PB remained strongly ultra-Left.

On the frontlines of the ultra-Left trend were the “Russian returned students” (the so-called “28 Bolsheviks”)—about 40 young Party members such as Qu Qiubai, Li Lisan and Chen Shaoyu (Wang Ming). They had completed their studies in Soviet Russian universities and returned to China, but otherwise were lacking in practical revolutionary work. They dominated the Party CC. They were also called the “Internationalists” together with Zhou Enlai due to their wider exposure to the proletarian-socialist movement in other countries.

By 1929, Li Lisan became the real Party leader, supported by Qu Qiubai. (The new general secretary, Hsiang Chung-fa, exercised his functions only nominally.) Li Lisan, as the most influential PB member within the Sixth CC, laid down his own “Left” opportunist line, which would prevail in the CPC for four crucial months from June to September 1930. On 11 June, under this ultra-Left influence, the PB issued the resolution “The New Revolutionary High Tide and Winning Victories at First in One or More Provinces.”

A single spark can start a prairie fire. Mao, around this time, was fighting too against the creeping undercurrent of pessimism. He too was brimming with optimism about the approaching “new revolutionary high tide” as an objective reality. But, in contrast to Li Lisan and the other ultra-Leftists, who dreamed of a quick succession of victories, Mao used a different framework that emphasized developing guerrilla warfare and Red political power in the rural areas.

In his famous letter, “A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire,” written on January 5, 1930, Mao agreed that that “there will soon be a revolutionary high tide in China” and that specific provinces like Jiangxi were ripe for the taking. But he clarified that it was erroneous to set a short timetable in this regard (e.g., to take Jiangxi within one year). In a classic case of a dialectical balance between recognizing the prospects in a general trend and realizing the hard work and intense struggles still needed to be won, Mao explained:

How then should we interpret the word “soon” in the statement, “there will soon be a high tide of revolution”? This is a common question among comrades. Marxists are not fortune-tellers. They should, and indeed can, only indicate the general direction of future developments and changes; they should not and cannot fix the day and the hour in a mechanistic way. But when I say that there will soon be a high tide of revolution in China, I am emphatically not speaking of something illusory, unattainable and devoid of significance for action. It is like a ship far out at sea whose mast-head can already be seen from the shore; it is like the morning sun in the east whose shimmering rays are visible from a high mountain top; it is like a child about to be born moving restlessly in its mother’s womb.

Mao strongly pushed for extending the base areas by advancing in waves; dividing the Red Army to arouse the masses and concentrating its forces to deal with the enemy; and arousing “the largest numbers of the masses in the shortest possible time and by the best possible methods.” He emphasized guerrilla tactics in dealing with the enemy: “The enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue.” When “pursued by a powerful enemy,” he said, the Red Army must “employ the policy of circling around.”

These concepts in waging armed struggle were, in fact, already the kernels of the future comprehensive strategic line of “encircling the cities from the countryside” in a protracted people’s war. On the other hand, Li Lisan so greatly belittled this approach, it was said, that he remarked, “Our hair will be white before the revolution is victorious” should Mao’s strategy and tactics be followed.

Ultra-Leftist drive for quick victory. Unlike Qu Qiubai’s obsession with urban uprisings, Li Lisan’s ultra-Leftism was in the conduct of the Red armies, rural soviets, and underground work in White areas leading to the expected “new revolutionary high tide.” Its most basic error was in denying the basic requirements for building mass strength, including the long and complex process needed to accumulate local victories and attain relative evenness.

The Li Lisan line was wrong on many levels. Essentially, it was no different from Qu Qiubai’s ultra-Leftism because it also over-relied on the expected confluence of certain positive but external factors—such as Soviet support, intensifying warlord rivalries, and the Great Depression which was turning into a global crisis—to artificially hasten the ripening process towards achieving nationwide victory within a short period.

The practical result was that, in violation of the Sixth Congress decisions, the Party was again rushed into an adventurist plan to gear for insurrections in many key cities of China. It pushed for the concentration of Red Army units for major offensives on cities, which would be coupled with “all-industry general strikes”, peasant uprisings and KMT army mutinies, in the hope that these offensives would trigger a victorious nationwide revolution.

Many Party cadres, especially those in the field leading the Red armies and Red areas such as Mao, opposed or raised serious questions about the Li Lisan line. But they were overruled by the pro-Li Lisan leadership, which went ahead with the military adventurist plans.

The 1930 insurrection. The planned 1930 insurrection aimed to seize political power in three big cities of Central China: Changsha (capital of Hunan), Wuhan (capital of Hubei) and Nanchang (capital of Jiangxi) through large-scale maneuvers and operations of the fledgling Red Army. Its I Corps (20,000 men) was to seize Nanchang, then join up with the II Corps and III Corps to seize the three Wuhan cities.

Alongside these, the CPC called on workers to launch strikes, which would then be transformed into armed uprisings in all big cities of the Yangtze valley, in Guangdong, and in Manchuria. Provincial Party committees and even mass organizations were “militarized” into action committees and militia formations that would lead the insurrectionary masses.

The Party leadership grossly overestimated its forces and the response of the masses. The III Corps was able to seize Changsha on 27 July. Here, on August 1, a soviet government of Hunan, Hubei and Jiangxi was proclaimed and a 10-point program promulgated. However, on 5 August (after just 10 days), KMT forces counter-attacked and drove out the Red forces. The I and III Corps were ordered to attack Changsha again in the first week of September but failed to retake it and withdrew by 13 September, while the II and IV Corps (which had been converging on Wuhan) also failed to attack its three cities due to intensified KMT defenses.

The uprisings in all the target cities failed right at the start. The KMT forces countered with intense suppression, which destroyed the CPC’s local organizations and Party-led workers’ unions in the said cities. (It was at this time that Mao’s wife and sister were executed among with many other CPC activists and Red fighters.) The Li Lisan line was thus proven wrong and disastrous in practice.

3.2 Decisive shift to the countryside, Wang Ming’s ultra-Leftism

The 3rd Plenum of the 6th CC was held in Lushan, Jiangxi in 24-28 September 1930. There, significant aspects of the ultra-Left line were criticized, Li Lisan admitted his mistakes, and positive measures were adopted to rectify specific errors. But the criticism against ultra-Leftism as a whole remained half-baked. Party leaders led by Wang Ming (Chen Shaoyu), who were “Russian returned students” like Li Lisan, remained dominant in the CC and pushed their own brand of “Left” opportunism.

From 1931 to 1934, Wang Ming’s line took the form of military adventurism. Despite the huge advances made during this period, the intense military situation brought out the worst aspects of Wang Ming’s adventurism on military questions, which in turn led to the biggest setbacks and damage to the Chinese new-democratic revolution.

Party reorganization. Wang Ming’s ultra-Leftism became dominant within the Party starting at the 4th Plenum of the 6th CC in January 1931. In that plenum, the CC agreed with Wang Ming’s “The Struggle for the CPC’s Further Bolshevization,” which continued, restored, or modified many aspects of the Li Lisan line and other ultra-Left ideas and policies as well.

That same month, however, a KMT crackdown netted 36 CPC members in Shanghai, of which 23 were later executed. In June, the nominal Party general secretary (Xiang Zhongfa) was also arrested and executed in Shanghai—prompting CPC leaders to decide to abandon their urban base except for a skeletal force (a bureau for White-area work). One effect was that Wang Ming became Party head by default.

In August 1931, Wang Ming returned to Moscow as head of the CPC delegation to the Comintern, but continued to exert a dominant influence in pushing his ultra-Leftist line in China. From the September 1931 reorganization through 1934, Qin Bangxian (Bo Gu) was the effective head of the CPC, with Zhang Wentian (Luo Fu), Zhou Enlai, Ren Bishi, Kang Sheng and Chen Yun as the other PB members, who in turn led a CC of some 20 members.

Through 1931-32, the Party center gradually shifted from Shanghai to the Red areas in southern Jiangxi and Hubei-Henan-Anhui (E-Yu-Wan), in order to directly lead the expanding Red areas and armies. Zhou Enlai held two key Party posts: he headed both the CC’s Military Affairs Committee and the Central Bureau for Soviet Areas (replacing Mao). Zhu De and Mao held key posts in the Red Army’s political department.

In 1933, the CPC could claim 300,000 members—of which around 140,000 were in the Red base areas while a fluctuating number from 10,000 to 60,000 worked in KMT-controlled (White) areas. The CPC had a secretariat, major CC departments, central bureaus for Red areas and White areas, five regional bureaus, army committees and provincial committees. Below these were district, county, or other area committees, and below them, local branches and cells.

The Communist Youth League (CYL) leadership worked closely with the Party CC, and held its Sixth through Tenth congresses in the 1931-34 period. It claimed a membership of 60,000 in 1933, and 100,000 in 1934—plus another 400,000 each in younger teenage and children’s groups.

The CPC published as many as 77 periodicals (34 in the Central Soviet alone) for its various propaganda needs.

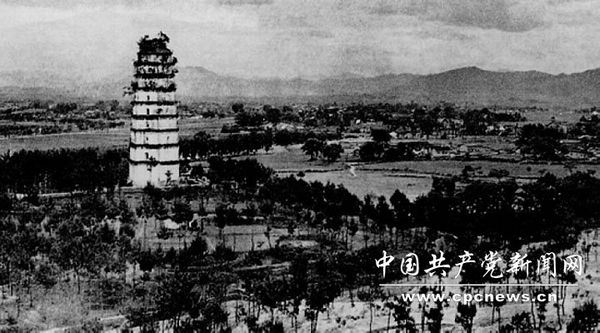

Chinese Soviet Republic. On 7 November 1931, the First National Congress of the Chinese Soviet Republic was held at Ruijin (seat of the Jiangxi central base), attended by more than 600 delegates from the various Red Army units, local soviets, and mass organizations including the National General Labor Union. It proclaimed the setting up of a provisional central revolutionary government encompassing all Red areas. By 1932, the Soviet Republic claimed to encompass 60 counties nationwide—of which 21 were in the central base area with a population of 2.5 million.

The new Red government approved a new agrarian law that rightfully made adjustments on land confiscations to limit the target only to landlords. This was in contrast to the previous Jinggangshan-period policy, which included rich and middle peasants as targets and made them unnecessarily hostile to the revolution. The new Soviet agrarian policy generated a lively mass movement for economic reforms and war production among the peasantry.

A significant bulk of Mao’s early writings on economic work date from this period. These include “Our Economic Policy” (23 January 1933), “Pay Attention to Economic Work” (20 August 1933), “How to Differentiate the Classes in the Rural Areas” (October 1933), and “Be Concerned with the Well-Being of the Masses, Pay Attention to Methods of Work” (27 January 1934).

In 1930, the CPC could still claim leadership over the National General Labor Union, which had more than 114,000 members, although more than half of these were in the Red areas and mostly categorized as farm workers and semiproletarians. By early 1934, more than 200,000 (or 90% of all proletarians and semiproletarians in the Red areas) were organized into three trade unions: one for farm workers, another for shop hands or artisans, and a third for coolies (unskilled laborers).

3.3 The Red areas and mass base-building

The major Red base areas that thrived across China during this period include the following:

Northern China (in Shaanxi, parts of Shanxi and Hebei). In northern Henan, CPC-led uprisings broke out in the late 1920s, while CPC and YCL branches formed in southern Hebei and western Shandong (Nankung-Weishien area) in 1930, claiming several thousand members by the mid-1930s. In July 1931, some 1,000 KMT troops mutinied in Shanxi, reorganized into the XXIV Corps of the Red Army, and moved into Hebei to form the first Red area in North China. Although it lasted only for a month, the area would revive later as a major Red area in the war of resistance vs Japan.

In Shaanxi, from the 1928 uprisings emerged the Red Army’s XXVI Corps led by Liu Zhidan, Gao Gang and others, with a local CPC membership of 800 (reaching 3,000 by 1933). In June 1932, they set up a base area in northern Shaanxi near Xi’an. Although the area quickly collapsed, by 1934 its remnants reestablished a new Red area further north—in the Paoan area where the Long March forces would arrive and link up with them.

Manchuria. Here, a Party committee for Manchuria was formed in November 1928. From 1932 onward, the Manchuria committee was based in Harbin with four subcommittees, three special committees, 12 county committees, and 17 city branches. In 1934, there were some 1,700 CPC members and 1,500 YCL members in all of Manchuria. Korean communists (including Kim Il-sung) were encouraged to work within these Manchuria units prior to setting up their own KCP organizations.

The CPC-led forces started guerrilla operations against direct Japanese aggression, and persisted despite repeated setbacks due to brutal fascist repression and internal weaknesses. CPC-led guerrillas, 10,000-strong in 1933, were in the frontlines of the anti-Japanese armed resistance as the Northeast People’s Revolutionary Army. (It was later transformed into the Northeast Anti-Japanese Army in 1936.)

Central China. Forces of the failed 1927 Autumn Harvest uprising led by He Long established a guerrilla base in northern Hunan and southern Hubei, which later expanded into western Hunan. (This would later become the core of the Second Front Army.) In 1929, they moved east to link with other guerrilla forces, then farther east around Hung Hu. In 1930, they suffered heavy losses (down to 3,000 from 15,000) during the Li Lisan-directed attacks on Changsha and Wuhan. Retreating to Hung Hu, they renewed Red area expansion and recruited 10,000 more troops by 1931. During the 1st KMT “encircle and suppress” campaign, they were reduced again to 600. Then they bounced back in 1932 to 18,000 Party members and 10,000 Red fighters, establishing the Hsiang-O-Hsi Soviet.

Jiangxi central base. The CPC’s main forces based themselves in the Central Soviet, or central base area, with its bulk in southern Jiangxi and western Fujian, and projecting its influence to neighboring provinces. From their original Jinggangshan base, the forces of Mao and Zhu De advanced farther east and established the Fujian-Guangdong-Jiangxi (Min-Yueh-Kan) soviet. Its main armed forces were Lo Pinghui’s XII Corps and Lin Biao’s I Corps, which would later form the core of Zhu De’s First Front Army. The central base was about 160 km by 240 km, and had its headquarters in Ruijin, Jiangxi. The Jiangxi central base also administered or closely coordinated with the other nearby bases.

Other Jiangxi bases. Surrounding the central base area were other, smaller Red areas:

- The Hunan-Jiangxi (Xiang-Gan) base, where the original Jinggangshan base was located;

- To its north, the Hunan-Hubei-Jiangxi (Xiang-E-Gan). The two bases in western Jiangxi (Xiang-Gan and Xiang-E-Gan) had a combined Party membership of 10,000 in late 1931, and could hold a Soviet congress in June 1932.

- In northeast Jiangxi and along the borders with Zhejiang, Anhui, and Fujian, the forces of Fang Zhimin established a Red base area which, in March 1931, became the Jiangxi-Fujian-Anhui, and later the Fujian-Zhejiang-Jiangxi (Min-Zhe-Gan) Soviet. Fang’s X Corps had 3,000 troops and would dramatically expand throughout the 1930s.

Hubei-Henan-Anhui. Next to the Jiangxi central base in terms of size and stable continuity in the early 1930s was the Hubei-Henan-Anhui base, also known as the E-Yu-Wan (Oyüwan) border region. Its guerrilla forces, created from the local peasant uprisings of 1927-29, went on to control 11 counties in the border of these three provinces. CPC membership grew to 7,000 members (and 4,000 YCL members) by early 1931. Its soviet government represented nearly 2 million people, and held two congresses in July and November 1931. Its armed forces grew from 1,000 in 1929 to 5,000 in 1930. Then, it dramatically rose to 30,000 or more in late 1931 and reorganized into the Fourth Front Army led by Xu Xiangqian and Zhang Guotao.

Sichuan. In summer 1932, the E-Yu-Wan base shrunk due to repeated KMT campaigns, and the Fourth Front Army—now reduced to 16,000—moved to the west and north still under Xu Xiangqian and Zhang Guotao. Reaching southern Shaanxi and northeast Sichuan, and reduced to 9,000 troops, it established the Sichuan-Shaanxi base in December 1932. Its forces grew to 50,000 by mid-1933, and by early 1934 covered 20 counties with a population of 9 million.

Far south China. In the early 1930s, CPC-led guerrilla forces (at times reaching several thousands) operated on Hainan island, and persisted in the area until 1949. On the Guangdong-Fujian border, the remnants of the old Hailufeng soviet (the very first Red area established on Chinese soil) reorganized into the XI Corps, with 5,000 troops by 1930. The “Left and Right River” Red area of Guangxi near the Vietnamese border, established in late 1928, collapsed by mid-1930. Its remnant forces were absorbed into the Central Red base area. There were also CPC efforts to organize local forces in Taiwan, the Philippines and Thailand, in addition to contacts with the Indochinese Communist Party.

Mass base-building. Despite the ultra-Leftist line pushed by the Li Lisan and Wang Ming leaderships, CPC cadres and members in the field began to give great attention to building mass organizations and local Party units in the rural Red areas. The lessons they learned were later summed up into the principle, policies and methods of the “mass line”, with Mao as its foremost proponent in his 1933-34 writings and talks.

While the revolutionary situation was ripe for building Red power in many localities of rural China, the CPC’s forces faced immense difficulties in reconnecting with the masses because of the costly ultra-Leftist errors related to the conduct of uprisings and premature offensives to take cities. The KMT took advantage of these CPC difficulties to intensify “encircle-and-suppress” campaigns.

Nevertheless, from 1930 onwards, the CPC realized the crucial need to give more attention to agrarian revolution (especially more practicable agrarian policies), the peasant movement, mass mobilizations at various levels in support of the revolutionary program, and activist recruitment and training for the people’s militia (“Red Guards”, ages 16-40), youth vanguards (ages 15-21), children’s corps, women’s corps, poor peasant associations, and labor unions.

Mass base-building also included economic work and cooperatives in the base areas and elsewhere (on which Mao gave special focus, as earlier mentioned in Subsection 3.2), running public schools, and many types of networked groups directly contributing to the war effort (e.g. support in logistics, medical and intelligence), and mass political education. [The details of agrarian revolution in the Jiangxi period have been left out for a future primer.—PRISM Eds.]

Throughout the early 1930s, the Red area governments drew mass activists into various cadre training institutes and programs, including civilian cadre schools and military schools (including the Red Army Academy), to continually infuse fresh young blood into Party, government, and army units at all levels.

Building the Red Army. Base building in the Red areas translated to advances in army building, and vice versa. The more the Red armies grew stronger, the more they were able to expand the Red areas, defend these against KMT attacks, and assist in base consolidation. The estimated total strength of fulltime army units grew in leaps and bounds: from less than 10,000 (in 1928), to 22,000 (in 1929), to 66,000 (in spring 1930), to as many as 200,000 (in 1932) and even as high as 300,000 (in late 1933).

By 1932, the main Red Armies in and around Jiangxi were the First, Second, and Fourth Front Armies. As many as 20 smaller detached units, which operated in far-flung guerrilla bases from Manchuria to Guangxi and Hainan, were incorporated into these three front armies.

- The First Front Army (formerly the Fourth Red Army, then I Corps), 100,000-strong in 1933, operated in southern Jiangxi. It was led by Zhu De as commander and Mao as political commissar.

- The Second Front Army, 10,000-strong in 1932, operated in Hung Hu and later in Hsiang-O-Hsi. It was led by He Long.

- The Fourth Front Army (formerly the First Red Army, then IV Corps), 60,000-strong in 1932, operated in the E-Yu-Wan base area. It was led by Xu Xiangqian, Xu Haidong and, later, Zhang Guotao.

The Red armies were organized from the level of divisions and regiments downward to basic squad-sized units of 10 Red fighters each. Political departments were created in large units and political officers assigned to the smallest units. Their work was to supervise political training, raise the soldiers’ political consciousness, and undertake political work among the local population. In early 1934, nearly 45% of the Red fighters were members of the CPC or YCL. In terms of age, 51% were 15-22 years old, while 44% were 23-49 years old.

By the spring of 1931, major Red Army units were already using radio communications to coordinate with the Party center and among themselves.

Successful guerrilla warfare vs first three KMT “encirclement and suppression” campaigns. In response to the failed 1930 insurrection, the KMT conducted a series of military “encircle and suppress” (EAS) campaigns against the CPC, its Red army and Red areas.

The first EAS campaign targetted the southern Jiangxi base area in November-December 1930. By January 1931, its Red Army (40,000 led by Mao and Zhu De) had defeated the 100,000-strong KMT forces, although it was also reduced to 30,000.

The KMT launched the second EAS campaign against the same Jiangxi base in February-June 1931. Despite employing 200,000 to strike deep into the central base, again the Red Army repelled the attacking KMT forces. In the third EAS, Chiang Kaishek personally led the 300,000-strong KMT force against the Red Army. Again, the KMT forces were beaten back.

Thus, the first three EAS campaigns did not last long and eventually failed. The Red Army, while much smaller and weaker, were able to inflict intense blows against the KMT armies. Under the leadership of Mao and Zhu De, the Red Army followed a correct military line of guerrilla warfare supported by the masses.

The Red Army’s basic operational principle for guerrilla warfare was eventually popularized as the 16-character formula: “The enemy attacks, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue”. It was accepted by the Party CC and served to guide the Red Army in defeating the first three EAS campaigns. From the kernel of this simple formula, which was repeatedly enriched in practice, emerged other principles of guerrilla warfare that would later form important components of Mao’s general line of protracted people’s war.

As Mao recounted in his work, “Problems of Strategy in China’s Revolutionary War” (December 1936):

At the time of our operational counter-campaign against “encirclement and suppression” in the Kiangsi base area, the principle of “luring the enemy in deep” was put forward and, moreover, successfully applied. By the time the enemy’s third “encirclement and suppression” campaign was defeated, a complete set of operational principles for the Red Army had taken shape. This marked a new stage in the development of our military principles, which were greatly enriched in content and underwent many changes in form, mainly in the sense that although they basically remained the same as in the sixteen-character formula, they transcended their originally simple nature.

3.4 Enormous damage caused by Wang Ming’s ultra-Leftism

Military adventurism worsens during the 4th and 5th KMT campaigns. Starting in January 1932, the CPC’s Wang Ming leadership belittled and criticized these operational principles of guerrilla warfare as “guerrilla-ism.” It issued the ultra-Leftist resolution entitled “Struggle for Victory First in One or More Provinces After Smashing the Third ‘Encirclement and Suppression’ Campaign”.

The ultra-Leftists insisted that “luring the enemy in deep to attack him with a superior force” was wrong “because we had to abandon so much territory”, while it was “better to defeat the enemy in his own territory”. They also pushed the policy of “maintaining a great rear area and an absolutely centralized command.” As Mao later wrote:

The new principles were the antithesis of the old. They were: “Pit one against ten, pit ten against a hundred, fight bravely and determinedly, and exploit victories by hot pursuit”; “Attack on all fronts”; “Seize key cities”; and “Strike with two ‘fists’ in two directions at the same time”. When the enemy attacked, the methods of dealing with him were “Engage the enemy outside the gates”, “Gain mastery by striking first”, “Don’t let our pots and pans be smashed”, “Don’t give up an inch of territory” and “Divide the forces into six routes”.

When the KMT launched its fourth EAS campaign against the central base area in Jiangxi, the Hubei-Henan-Anhui and the Hubei-Hunan base areas after mid-1932, the Red Army could again defeat the KMT armies but not as fully as the earlier counter-campaigns. The KMT attacks against the Jiangxi central base were defeated by early 1933. But the Red victories were costly, as numerous other small Red bases were lost in the process.

Finally, in October 1933, the KMT launched its fifth EAS campaign against the Jiangxi central base. It employed some 750,000 NRA troops, with aircraft and German military advisers. The defense of the base area turned into a debacle, and the Red armies had to leave the main Red areas in the south a year later, in 1934.

Wang Ming’s ultra-Leftism worse than Li Lisan line. Wang Ming’s ultra-Left line dominated the CPC all the way to the midst of the Long March in 1935. In the history of China’s new-democratic revolution, Wang Ming’s wrong line prevailed the longest and brought the worst damage to the Party, the people’s army, and the revolution’s mass base.

The worst features of Wang Ming’s ultra-Leftism included: re-labelling the Li Lisan line as Right instead of ultra-Left; insisting that the main danger within the Party was Right deviations; exaggerating the role of capitalism in China’s economy; denying the existence of middle forces, parties and groups; overstating the existence of a revolutionary high tide and the imminence of an “immediate revolutionary situation” in one or more provinces and key cities, which was the basis for the policy of launching offensives on a nationwide scale; and insisting that a “real” Red Army and “real Soviet government of workers, peasants and soldiers” did not yet exist.

Wang Ming’s group of “28 Bolsheviks” also practiced a policy of “ruthless struggle” and “merciless blows” in resolving differences within the Party. Those who did not accept these policies were labelled as “opportunist” and meted disciplinary action. For example, they removed Mao from his leading post in the Red Army, because he was conducting a principled ideological struggle against their ultra-Left line.

CC plenum heightens ultra-Leftism. In January 1934, amidst the ever-tightening military situation, the Fifth Plenum of the 6th CC and the 2nd National Congress of the Chinese Soviet Republic were held back-to-back in Ruijin. The Party CC expanded to 29, and elected a 14-member PB and a five-member Standing Committee (both of which did not include Mao). The SC was composed of Bo Gu, Luo Fu, Zhou Enlai (who also headed the Military Affairs Committee), Xiang Ying, and Chen Yun.

In their policies and organizational measures, both the Fifth Plenum of the 6th CC and the Second Congress of the Chinese Soviet further advanced the ultra-Leftist line, pointed to “Right opportunism” as the main danger, and criticized the correct line advocated by Mao, Lo Ming and others as “conservatism.” Mao retained his post as chairman of the Central Soviet EC, but his authority was diluted by the addition of more ultra-Leftist leaders.

4. What was the overall situation nationwide and in the White Areas?

4.1 Developments in the national situation and in the White areas

By end-1928, the new KMT warlord regime had defeated the previously dominant Northern warlord cliques, and fell under the leadership of Chiang Kaishek’s Whampoa clique and the Guangxi warlord clique. It remained a regime of the comprador-landlord ruling classes, replaced the old warlords with new ones and further capitulating to the imperialist powers.

Chiang’s new KMT warlord regime effectively controlled only about five provinces in the lower Yangtze valley. Elsewhere, various warlord cliques challenged KMT rule; armed rebellions erupted yearly from 1929 to 1931. The fascist KMT regime brutally repressed attempts to establish reformist “third parties” that tried to tread a middle ground.

White terror and warlord rivalries. The Chiang regime subjected the masses of workers, peasants and other sections of the people to even more ruthless exploitation and oppression. In the cities, KMT security forces infiltrated CPC-linked organizations and arrested tens of thousands, including leading CPC cadres, and executed most except the handful that turned traitor through bribery or coercion.

From April 1927 to 1937 (i.e., before the second KMT-CPC united front was formed), the KMT claimed to have arrested 24,000 Communists and more than 155,000 “Red masses,” while the CPC estimated that the KMT butchered some 300,000 people across China. In many bulwarks of the CPC, entire communities were uprooted and whole families killed, including infants. Many women were sold to prostitution.

The four cliques of the new KMT warlords (Chiang Kaishek, the Guangxi warlords, the “Christian general” Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan) had earlier formed a temporary alliance against Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin. But as soon as they captured Beijing and Tianjin in June 1928, the alliance gave way to fierce struggles among the four cliques. These rivalries reflected the rivalries among the imperialist powers that were dividing China among themselves.

4.2 Growing Japanese aggression

Jinan massacre. In 1928 Chiang Kaishek, backed by British and US imperialism, drove north to attack the Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin. The Japanese imperialists, to check this northward spread of their British and US rivals, in turn occupied Jinan (capital of Shandong province). From May 3 to 11, the invading Japanese troops slaughtered large numbers of people in what became known as the Jinan Massacre. In June 1928, while retreating to the Northeast by rail, warlord Zhang Zuolin was killed by a bomb—planted by the Japanese imperialists whose tool he had been.

Mukden and Eastern Hebei incidents. Chiang Kaishek, despite posturings that he would resist Japan’s increasingly bloody intrusions, brazenly compromised with the occupying Japanese forces. On 18 September 1931, the Japanese “Kwantung Army” in northeastern China seized Shenyang. In line with Chiang Kaishek’s capitulationist order of “absolute non-resistance”, the KMT’s Northeastern Army troops retreated south.

What is now known as the Mukden incident enabled the Japanese aggressors to rapidly occupy the three provinces comprising Manchuria (Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang) by 1932. They seized the fourth northeastern province of Jehol (now Rehe) in 1933, and set up a puppet regime headed by a KMT traitor called the “Eastern Hebei Anti-Communist Autonomous Administration” in November 1935.

Chiang’s response to Japanese aggression was a weak position of “first pacification, then resistance.” It emphasized first, control of KMT internal factions and strengthening the NRA, second, control of internal developments (especially the CPC threat), and third, getting foreign help. As reflected in its budget, Chiang’s KMT regime prioritized the defeat of the Red Army, in effect hindering unity vs. Japan. In contrast, as early as 1932, the CPC forces had already declared war vs. Japan and later offered concrete proposals for an anti-Japanese united front.

4.3 Developments in the broad mass movement

In the face of worsening imperialist aggression, warlord conflicts and the Chiang regime’s White terror, labor strikes in the cities (estimated to have involved more than 1 million workers in 1932 alone) and peasant insurrections in the rural areas continued to grow. This showed that the CPC’s wide influence among the toiling masses remained, even if it could no longer claim direct leadership due to its underground operations.

The CPC also made inroads among urban students and intellectuals (including many leading literary figures such as Lu Xun). They organized the League of Left-Wing Writers in March 1930 and other radical groups such as the League against Imperialism, the Japan-China Struggle League, and the International Red Relief.

The Jinan massacre, the Japanese occupation of Manchuria, the Eastern Hebei and other incidents fanned the growing flames of the revolutionary and patriotic movements across China. Although most of the national bourgeoisie had participated in Chiang Kaishek’s 1927 anti-communist coup d’état, one group gradually began to oppose his regime. This KMT faction, led by Wang Jingwei and other counter-revolutionary careerists and later became known as the “Reorganization Clique”, urged sections of the national bourgeoisie to pursue a strong reform movement in the coastal areas and along the Yangtze River. Meanwhile, the hunger and cold created great unrest among the warlord armies’ rank and file, which remained very open to agitation by the CPC and its Red armies. ■

Forthcoming: Part 4 – The Long March (1934-1936)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!