Paris Commune as early example of proletarian internationalism

By ANDI BELISARIO, PRISM Contributor

The 1871 Paris Commune encouraged, officially and in practice, the participation of non-French nationalities in its many concerns, both in decision-making and in actual ground-level actions. Thus it was not only following the internationalist tradition of the 1848 Revolution, but strengthened it further. Increasingly, its internationalism advanced along proletarian-socialist lines, especially thanks to the direct role of many members of the International in the Commune’s leadership.

The Commune’s internationalist spirit was upheld right at the outset. On 30 March 1871, just four days after the Paris population elected the 92 delegates to the Commune, the elections commission which validated the vote confirmed the citizenship of the foreigners elected to the Commune. It reiterated the principle that “the flag of the Commune is the flag of the Universal Republic”.

The role of the International Workingmen’s Association

The International Workingmen’s Association (or, International) played a key role in emphasizing the proletarian-internationalist character of the Commune. It mobilized veterans of the 1848 Revolution (which was Europe-wide), political refugees from as distant lands as Russia, and immigrant workers and their families who came from other parts of Europe.

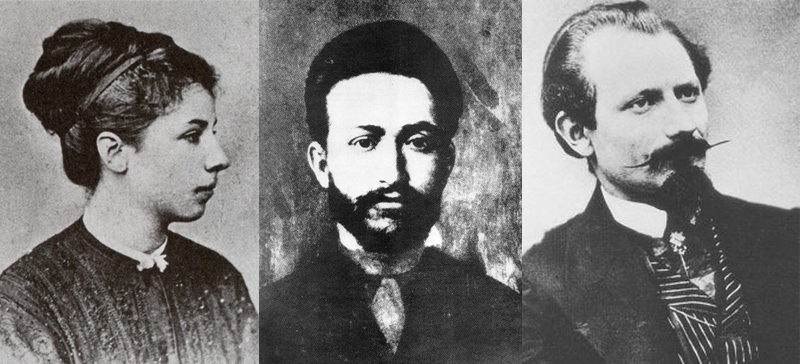

Among the foreigners engaged in the Commune, many were already worker-activists who were members of the International and considered themselves socialist revolutionaries. Commune leaders like Leo Frankel of Austria-Hungary, veteran Polish revolutionaries Jaroslaw Dombrowski and Walery Wroblewski, Elisabeth Dmitrieff and many other Communards from other nationalities raised high the banner of the world proletariat and fought in the barricades alongside their French comrades-in-arms.

Throughout its duration, the Commune aroused tremendous sympathies and received countless expressions of support from the working classes of other countries. Much of this support was solicited and facilitated by the International through its country sections in the rest of Europe and in America.

Once the Commune emerged, Karl Marx unreservedly supported it from start to end. He and Friedrich Engels could not directly join the Commune since they were based in England, as were other leaders of the International. Instead, the two communist leaders rallied the rest of the International, utilized all accessible information channels and organizational networks to reach out to the rest of the world, and gather international support for the Communards.

Responding to Frankel and Varlin (two influential leaders of the Commune and also members of the International) who wrote Marx for advice and aid, he replied: “ … For your cause I have written some hundreds of letters to all the corners and ends of the world, wherever we have connections.”

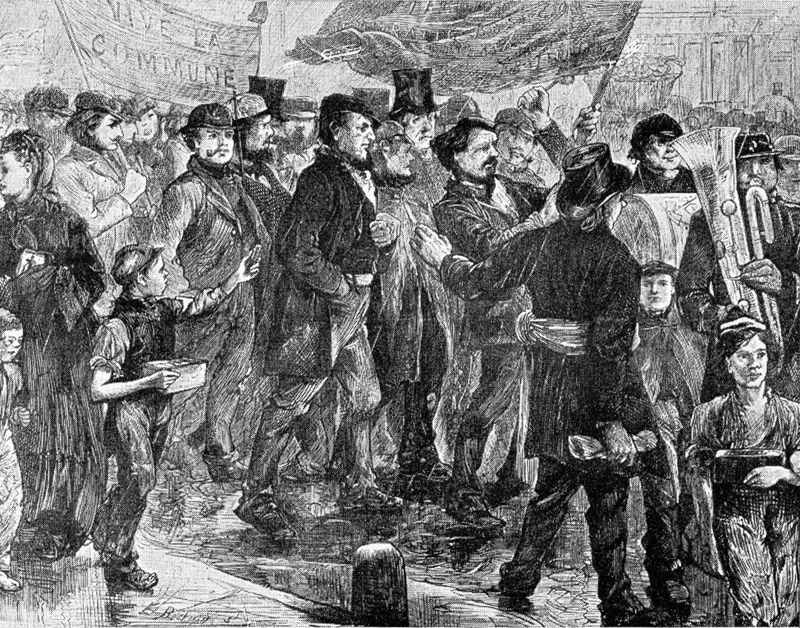

Workers’ demonstrations of support for the Commune broke out in many countries of Europe.

Working-class leaders and organizations in Germany were especially passionate in their support of the Paris Commune, being aware that the bloodthirsty French regime in Versailles was tightly intertwined with the German armies in strangling the Commune. German communist leader and parliamentarian August Bebel vowed thus:

… Be assured that the entire European proletariat, and all that have a feeling for freedom and independence in their heart, have their eyes fixed on Paris. And if Paris is for the present crushed, I remind you that the struggle in Paris is only a small affair of outposts, that the main conflict in Europe is still before us, and that ere many decades pass away the battlecry of the Parisian proletariat, war to the palace, peace to the cottage, death to want and idleness, will be the battlecry of the entire European proletariat.

Immigrant proletarians as a mass base of the Commune

In the decades preceding 1870-71, Paris and other French cities received a large number of immigrant workers, mainly from Switzerland, Belgium and Luxembourg. In Paris, they were concentrated in working-class districts such as La Villette, Belleville, and in the 13th arrondissement. Others were political refugees who sought sanctuary in France to escape prison and persecution in their homelands.

When the Paris Commune arose, these immigrant laborers and refugees together with their families did not think twice in lending support, directly participating in its actions, and in defending it until the end.

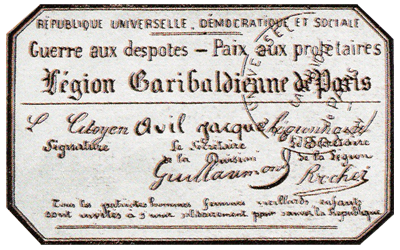

Many officers of the National Guard were Italian and Polish revolutionaries who had some experience in armed struggle. Some of them fought in the 1863 Polish insurrection for independence. Others fought with Garibaldi to attain Italian unity against the Church. These fighting men offered their services to the Commune, and were often elected as officers by the National Guard battalions themselves. The Commune also formed a Belgian federal legion, ready to join in the defense of Paris.

Source:

The Kabyle insurrection in Algeria, Zouave fighters in Paris

In Algeria, the Kabyle insurrection against the French colonial regime began on 15 March 1871—just a few days earlier than the Paris uprising. On 8 April, Sheikh Aheddad (elder religious chief of the Rahmaniya confederation) called for all Algerians to rise up in arms. Some 250 tribes responded by mobilizing their warriors into a 10,000-strong army led by El Mokrani. Uprisings spread like wildfire across the entire country and approached the very gates of Algiers.

The four Zouaves regiments, which were created by the French regime in 1830 after it conquered Algeria, were dissolved after Prussia’s victory at Sedan against France. In Paris, the National Guards fraternized with the Algerian troops who were sympathetic both to the Kabyle insurrection and to the Paris Commune.

The Kabyle insurgents supported the Paris Commune by issuing a communiqué on 28 March. They explained their own revolt in terms that Parisians readily understood: “The whole of Algeria is claiming communal freedoms.” The Commune received, welcomed, and published the Algerian statement of support on 18 April.

The Commune took moves to reorganize the corps of Zouaves of the Republic, many of whom fought alongside their French brothers- and sisters-in-arms. Until today, Parisians recall the popular story of Père Trankil, a Kabyle Zouave in the 13th arrondissement who joined the Commune on 18 April. He reiterated Algerian solidarity with the Parisians: “So the Algerian people have taken up arms in turn, we will soon have a universal republic!”

(Note: When the Paris Commune fell, the French authorities were thus able to free a big bulk of its forces and reconstitute a strong 100,000-strong African army led by Admiral Gueydon. The reinforced French colonial regime was thus able to subdue the Kabylia, like it did earlier in 1857.)

Outstanding foreign leaders of the Paris Commune

Jaroslaw Dombrowski

Jaroslav Dombrowski (or Jarosław Dąbrowski) was born in Jitomir, Poland on 12 July 1836, to parents of Polish nobility. He was a former Russian army officer, serving as quartermaster. Driven by patriotism and involved in Narodism, he was involved in the 1863 insurrection for Polish independence from Russia. Condemned to Siberian exile, he escaped and sought refuge in France.

When the Third French Republic was proclaimed on 4 September 1870, Dombrowski offered his military services. But like many internationalists with radical-proletarian sympathies, he was twice arrested instead.

Dombrowski joined the Commune from its very first day on 18 March 1871. He and fellow Polish revolutionary Walery Wroblewski were the only senior leaders of the Commune to have received military training (with the exception of Col. Louis Rossel). On 6 April, he was appointed commanding general of the 11th Legion of the National Guard. On 9 April onwards, he led his troops in defending Neuilly after the Parisian defeat at Courbevoie. He led the victorious counter-attacks of 11 and 12 April.

Dombrowski recommended the tactical use of artillery and the formation of flying commandos instead of preparatory bombardment and maneuvering infantry. But his ideas were disregarded both by Cluseret (Delegate for War at that time) and by other National Guard forces.

Adolphe Thiers, who knew Dombrowski’s leadership skills, discreetly sent him an emissary with an offer of 1.5 million francs in exchange of crossing over to the Versailles side. But the general exposed the attempted bribery instead, and ordered the emissary arrested and shot.

On 19 April, Dombrowski was wounded in action. Ten days later, he was given the command of all forces on the Seine’s right bank. Louis Rossel, who had replaced Cluseret as Delegate for War since 1 May, appointed Dombrowski on May 5 as the first commander-in-chief of the entire army of the Paris Commune—now reduced to some 40,000 disorganized troops. On 14 May, on Delescluze’s orders, he led his troops in building stone barricades within Paris.

On 22 May, when Versailles forces had broken through and had reached the Opera and the Arc de Triomphe, Dombrowski led a battalion through the rue de Rivoli, astride his black horse. Singing the Chant du Départ, his battalion charged at the enemy from the Town Hall.

On the afternoon of the next day, 23 May, after 11 days of fighting alongside his troops in the frontlines, Dombrowski received a lethal bullet wound as he was about to lead a brigade-sized counteroffensive from the barricade on rue Myrrha (east of Montmartre). He died a few hours later. Wrapped in a red shroud, he was buried with honors by his comrades-in-arms at the Père-Lachaise Cemetery on 25 May. He was nearly 35 years old.

Walery Wroblewski

Walery Wroblewski was born in Zoludek, Poland in 1836, to a family of the Polish gentry. He studied at the Institute of Water and Forests in St. Petersburg, Russia. (Poland was then annexed to the Russian Empire.) He took part in the Polish uprising of 1863, was wounded, and forced into exile in Paris by 1864.

In Paris, Wroblewski worked first as a lamplighter, then as a printing-press worker. During the years 1864-1870, he was active in the Committee of the Union of Polish Democrats. When Paris faced the Prussian siege in 1870, he proposed to create a Polish legion. This was rejected by the monarchist- and bourgeois-dominated Government of National Defense.

When the Paris Commune was established, Wroblewski was appointed commander of the fortifications of southern Paris between Ivry and Arcueil. Serving his command well, he was noted by most Parisians for his bravery and tactical acumen.

During the Bloody Week, Wroblewski led his troops in defending the Butte-aux-Cailles and then the Bastille district. After losing these two defensive battles, and with many other senior officers of the Commune either killed or wounded, he was offered the overall command of what remained of the Communard army. He refused, and instead spent the rest of the Bloody Week fighting as a rank-and-file soldier.

Wroblewski escaped the Paris bloodbath and was able to take refuge in London, where he joined the General Council of the International. He returned to France after the 1880 amnesty, but found it difficult to live there. He died in Ouarville (Eure-et-Loir) in 1908, at age 72, and was buried in the Père-Lachaise cemetery, near the Mur des Fédéré among his comrades-in-arms.

Elisabeth Dmitrieff

Elisabeth Dmitrieff (real name: Elizabeta Luknichna Tomanovskaya née Kusheleva) was born on 1 November 1850 in Volok, Pskow province, Russia (now in Toropetsky District, Tver Oblast). She was the youngest of three children, borne out of wedlock by a Tsarist official and a Lutheran sister of charity. Her older brother was involved in the revolutionary group Zemlya i Volya. At a very young age, Elisabeth showed sympathy to mistreated peasants and often met revolutionaries passing through the region.

Dmitrieff soon joined underground socialist circles in St. Petersburg. In 1868, she entered a “marriage of convenience” to be able to emigrate to Switzerland and attend university. In Geneva, she met other Russian revolutionaries, joined the Narodnoye Dyelo group, and co-founded the Russian section of the International.

The Russian section sent Dmitrieff to London to learn from the British workers’ movement and link with the International’s General Council. Here she met Karl Marx, with whom she discussed Russia’s socio-economic conditions. She soon became friends with him and his family, especially his daughters.

When the Commune was proclaimed in March 1871, Marx sent the 20-year-old Russian activist on a fact-finding mission to Paris as correspondent and representative of the General Council. She quickly became involved in organizing ambulance stations and canteens, and in pushing for the Commune to implement measures that advanced working women’s interests.

On 11 April, together with Nathalie Lemel and other proletarian women activists, she co-founded the “Women’s Union for the Defense of Paris and the Care of the Wounded” and linked it to the International. As general secretary of its Central Committee, she concentrated on political questions and the formation of cooperative workshops run by the workers themselves. Among its gains were the decree ensuring equal pay for working women and men.

Dmitrieff saw the Paris Commune as “the banner of the future” and “representing the international and revolutionary principles of the people” which, when they win, “working men and working women, in full solidarity with extreme effort, it will forever annihilate all traces of exploitation and exploiters.”

During the Bloody Week, Dmitrieff joined other Communards in fighting on the barricades of the rue du Faubourg-Saint Antoine and in bandaging wounded comrades. She went into battle armed with two pistols tucked into a red sash wrapped around her waist.

Dmitrieff managed to escape the Versailles troops and fled to Switzerland, where she sheltered other exiles for a time before returning to Russia. In 1872, she met Ivan Davidovsky—described in some accounts as a revolutionary, by other accounts as a member of a criminal group. In 1876 Davidovsky was arrested on criminal charges (murder, fraud and embezzlement). When she sought support from her old international friends, Marx found her a lawyer to help Davidovsky avoid the death penalty.

Dmitrieff legally married Davidovsky in 1877 upon his release under house arrest shortly before his exile to Siberia. She followed him to exile, where she spent the rest of her life until, at age 59, she died in 1910. (According to other sources, she divorced Davidovsky in 1910, returned to Moscow with her two children, and died probably in 1918.)

Sources: http://pelenop.over-blog.com/article-30450722.html, https://www.infoaut.org/storia-di-classe/23-febbraio-1919-elisabeth-dmitrieff-si-fermo-sulle-barricate

Leo Fränkel

Léo Fränkel born near Budapest, Hungary in 1844 to a Jewish family. He worked as a goldsmith-jeweler, and lived for a while in Germany and England, where he joined the International. In 1867, still working as a jeweler, he moved to Lyon and then to Paris, where he represented the German section of the International.

Fränkel was arrested in April 1870, faced trial with other activists of the International in July, and was sentenced to two months in prison for conspiracy and belonging to a secret society. He was freed after the Second Empire collapsed on 4 September 1870. He became a member of the National Guard, a member of the Republican Central Committee of the Twenty Arrondissements and, with Eugène Varlin, reconstituted the International’s Federal Committee for Paris.

On 8 February 1871, Fränkel ran as a revolutionary socialist but failed to win a deputy’s seat in the National Assembly elections. When the Paris Commune held its own municipal elections on 26 March, however, the 13th arrondissement elected him to the Council; he was just 27 years old. He became a member of the Labor and Exchange Commission, which was responsible for social concerns of the revolutionary Commune, then later of the Finance Commission.

On 20 April, Fränkel was appointed Work, Industry and Exchange Delegate. Under his watch, important social measures were decreed, such as the ban on night work in bakeries. On 1 May, he voted in favor of the controversial creation of the Committee of Public Safety, but quickly changed his mind and aligned himself with the minority in the Commune’s Council.

During the Bloody Week, he was wounded in the barricade fighting on the rue du Faubourg-Saint-Antoine, corner of the rue de Charonne, but was saved by Elisabeth Dmitrieff. He escaped the Versailles manhunt, took refuge in Switzerland, and then moved to England. On 19 October 1872, the French Council of War condemned him to death in absentia.

In England, Fränkel joined Marx and the International in 1872 in the fight against Bakunin’s anarchist faction. In 1875, he went to Germany but was expelled. Then he moved to Austria, where he was arrested in October. Released in 1876, he went to Hungary. There he organized the Workers’ Party in 1880. In March 1881, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison. Released once more in February 1883, he worked as a proofreader and contributed to the socialist review Gleichhet.

In 1890, Fränkel returned to France and participated in the founding Congress of the Second International. He contributed to the Vorwärts (German socialist newspaper) and to La Bataille of Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray. Remaining in proletarian poverty to the end, in 1896, he died of pneumonia in Paris at age 52. #

SOURCES

https://raspou.team/1871/les-etrangers-et-la-commune/, https://printemps1871.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/printemps-1871-nc2b01.pdf, https://www.rs21.org.uk/2021/03/31/1871-the-commune-and-the-kabylia/, http://pelenop.over-blog.com/article-30450722.html, https://www.infoaut.org/storia-di-classe/23-febbraio-1919-elisabeth-dmitrieff-si-fermo-sulle-barricate

Corrections (2021-04-28): The entire section on Elisabeth Dmitrieff was rewritten to include more details about her family background and political work in Russia, Geneva and London, and her later years after the Commune. Sources were added as Internet links.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!